Attenborough: 60 Years in the Wild

Attenborough: 60 Years in the Wild is a three-part BBC TV series that premiered in the UK in November 2012, and was shown in Australia in May 2013. It portrays highlights of Sir David’s 60-year career of making wildlife documentaries.

The first episode, ‘Life on Camera’, shows the developing excellence of his filming equipment and techniques. These range from the clockwork movie cameras used in the 1950s (which he says “made a noise like a cement mixer”), to modern video cameras used underwater, infrared cameras used for night-time shots of lions hunting, thermal cameras used to show the Galápagos marine iguanas sunning themselves, optical probes used to investigate ants’ nests, digital cameras and computers used to condense the arrival of Spring into a few seconds, and computer animation used to depict extinct animals.

However, we do not agree with his evolutionary storyline, which we believe is historically and scientifically wrong. This article will therefore deal with this aspect of his worldview, presented principally in the second episode of this TV series, entitled ‘Understanding the Natural World’. (Episode 3, entitled ‘Our Fragile Planet’, is on Conservation.)

Miller’s experiment1,2

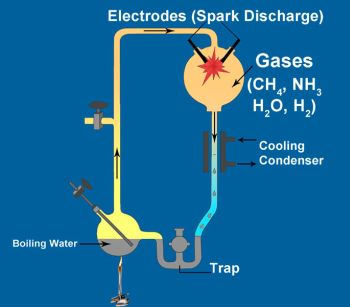

Sir David begins his exposition of evolution by telling viewers that “in the 1950s we knew next to nothing about the great mystery of all, the origin of life. And then, in 1952, a young post-graduate student at the University of Chicago, Stanley Miller, decided to try and re-create the conditions of the early earth in a laboratory.” In this experiment (which we show in the diagram), Miller passed a high voltage electric spark (simulating lightning) through a flask containing methane, ammonia, water vapour, and hydrogen (simulating Earth’s alleged earliest atmosphere). Then Attenborough says:

“A week later, he found a brown liquid in the bottom of his flask. It contained amino acids, the building blocks of life. Stanley Miller had demonstrated that the first steps on the path leading to life had happened spontaneously.”

Ever since then, this experiment has been heralded in textbooks and by the popular press as ‘proving’ abiogenesis or chemical evolution, i.e. that life can arise spontaneously from non-living chemicals. However, Miller had shown no such thing. In fact, the many problems in the experiment actually support the opposite view. These counter-indicators include:

- Most evolutionists today believe Earth’s early atmosphere was composed largely of carbon dioxide and nitrogen rather than the reducing gases assumed by the Miller-Urey model. These gases do not react to form amino acids.

- The atmosphere in Miller’s apparatus was oxygen-free, because oxygen would have combined explosively with hydrogen in the experiment. But large amounts of oxidized rocks occur in the Pre-Cambrian geological strata, indicating the early presence of oxygen.

- Miller used a trap to collect his end products. No such trap exists in nature. The products did not form in the flask, as there they would have been destroyed by the energy/radiation used by Miller to produce them. So this is illegitimate interference from an intelligent investigator.

- Miller’s end product was a tarry mixture, containing traces of fewer than half the 20 amino acids required for life.

- All of the few amino acids formed were a 50:50 mixture of right-handed and left-handed forms called a racemic mixture. This inhibits life. Living systems contain only left-handed amino acids.

- Amino acids can’t reproduce. A critical component of life is the information stored on DNA. This was absent from Miller’s products. Indeed, DNA is too unstable to last in any primordial soup without the repair enzymes of living creatures. The related molecule RNA is even less stable. Even their building blocks are unstable.

If Miller’s experiment shows anything, it is that life cannot form from non-life.3 God says that He created the atmosphere suitable to support life on Day 2 of Creation Week. He then created plant life on Day 3, animal life on Days 5 and 6, and human life on Day 6. The origin of life is a mystery only to those who disregard Genesis chapter 1.

Attenborough then suggests “a different location for the origin of life”.2,4 He shows an eco-system 2,000 metres underwater at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean consisting of giant tubeworms, small fish and crabs living among active volcanic vents, and he says: “Some of the dissolved chemicals were serving as food for bacteria; the bacteria nourished the tubeworms, and they in turn were food for crabs and fish.”

Then: “Clearly vents such as these could have supported the first micro-organisms that appeared in the primeval seas nearly 4,000 million years ago.”

Really! What micro-organisms? Also, the high temperatures of such hydrothermal vents would quickly break down organic molecules. Living creatures that live near such vents have elaborate repair systems.

Avoiding the unanswerable, Attenborough continues: “How did these early forms of life give rise to the great diversity of creatures that live today?” And he adds: “That problem has bothered thinkers since the very beginning of science.” The problem is acute, since the ‘periods’ they ‘date’ as very ‘early’, such as the Cambrian5 and Ediacaran, exhibit ‘explosions’, where many diverse groups of life appear abruptly. Well, it may have bothered atheists, but no such problem exists for creationists. God created plants and animals according to their kinds (Genesis chapter 1) some 6,000 years ago, and since then these created kinds have diversified into all the species we see today.

Darwin and natural selection

Attenborough then appeals to Darwin’s theory of evolution by means of natural selection, and says that in 1979, he used this theory as the basis for the TV series ‘Life on Earth’. His first example from this is to revisit the two types of tortoises Darwin saw on the Galápagos Islands—the dome-backed and the saddle-backed varieties.

However, as we pointed out in our response to his Galápagos TV series, natural selection is not evolution, but a culling process that ‘chooses’ from what is already there and exterminates unfavourable variations. In this case, the saddle-backed, longer-necked tortoises can survive on the grass-free islands because they can reach the tall cactus vegetation, whereas any dome-backed short-necked tortoises there would starve. This is a nice example of natural selection in operation, but it is adaptation within a species, not microbe-to-man evolution. Such adaptation will not turn gooey mush into Galápagos mega-reptiles.

See Galápagos with David Attenborough: Evolution.

Intermediate forms

1. The Australian lungfish

Darwinism requires intermediate forms, so Attenborough responds by offering the Australian lungfish. This, he says: “lives in water just like an ordinary fish, but it can also breathe air through a pouch in its throat like a simple lung. And it pumps itself along the river bottom, using two pairs of muscular fins placed low on its body, just like simple legs.”

However, research scientist Michael Denton (who is not a creationist) has a more accurate analysis of this species. He writes:

The lung fish … has fins, gills, and an intestine containing a spiral valve like any fish but lungs, heart and a larval stage like an amphibian. … Its fish characteristics such as its gills and its intestinal spiral valve are one hundred per cent typical of the condition found in many ordinary fish, while its heart and the way the blood is returned to the heart from the lungs is similar to the situation found in most terrestrial vertebrates. In other words, although the lungfish displays a bewildering mixture of fish and amphibian character traits, the individual characteristics themselves are not in any realistic sense transitional between the two types. … Between lungfish and amphibian there are tremendous gaps not bridged by any transitional forms.6

Nevertheless, Attenborough proceeds with: “Fossils of fish very like the Australian lungfish are known from rocks that are some 400 million years old. And we can be pretty sure that those ancient fish could breathe air.”

We dispute that any rocks are 400 million years old. And we can be pretty sure that when Attenborough says he’s pretty sure about anything, it means he is repeating what others have said but they and he do not have the evidence to support it.

2. Tiktaalik

|

|

|

Left: Tiktaalik on the cover of Nature, 6 April 2006. Right: Footprints ‘millions of evolutionary years’ older, as shown on Nature, 7 January 2010. Click each picture for a larger image. | |

Tiktaalik is Attenborough’s answer to the problem of how any ancient fish could have managed to get out of the water and onto the land. The fossil remains of this animal comprise a 20-cm-long fish skull and some fossil front fins, with digits roughly like those of land vertebrates—found in Arctic Canada in 2004. It was vigorously promoted by evolutionists as being the 375-million-year-old extinct transitional link that was on its way to becoming the first four-legged land vertebrate. In 2006, the fossil was featured on the cover of Nature, in which an article said, “ … this really is what our ancestors looked like when they began to leave the water.”7 Attenborough shows viewers the fossil limb with its digits and then says: “This almost certainly was the first limb to move a creature up onto land.”

Alas for Tiktaalik as a missing link, this assumption has been falsified. Several well-preserved footprints undoubtedly made by a four-legged animal were found in Poland in rock ‘dated’ at 18 million years older than Tiktaalik. In 2010, Nature admitted: “They force a radical reassessment of the timing, ecology and environmental setting of the fish–tetrapod transition … .”8

However, Tiktaalik (like ‘Lucy’) has entered the folklore of evolutionary story-telling, and we anticipate that evolutionists generally (including those who make TV wildlife documentaries) won’t drop it until they find something to replace it.

See

- Abandoned transitional forms.

- Tiktaalik roseae—a fishy ‘missing link’

- Tetrapods from Poland trample the Tiktaalik school of evolution

Distribution

Attenborough next asks: “Why is it that closely related groups of animals can occur on both sides of an ocean—in West Africa and South America for example?” His main example is frogs, but this is more of an exception than a rule. For example, in Africa there are leopards, rhinoceroses, giraffes and gorillas, but not in America. In America, there are raccoons, jaguars, armadillos and opossums. Evolutionists usually claim that this is because different animals evolved in different parts of the world.

Attenborough’s answer is much more interesting: maybe it wasn’t the animals that moved, but the continents. And he advances the idea (now generally believed by evolutionists) that the continents of the earth are fragments of a much larger super continent that over millions of years drifted apart. In support, he shows seashells that litter the high-up slopes of the Himalayas, which he says were raised to their present height “about 65 million years ago”. And he asks: “What forces could possibly have raised the sea floor to these heights?” His answer: volcanic action at the bottom of the sea.

The Bible doesn’t mention continental movement as such, but Genesis 1:9–10 could imply that God originally created one land mass. If there was only one land mass before the Flood, there would have been no problem about now-distant animals boarding the Ark. During the Flood, catastrophic plate tectonics (not today’s claimed drift rates of 2–15 cm per year) could have supplied the massive catastrophic geological processes that lifted up the Himalayas and other mountain ranges some 4,500 (not 65 million) years ago.

At the end of the Flood, those animals preserved aboard Noah s Ark spread out over the world, migrating via land bridges, with lower sea levels during the subsequent Ice Age. Thus animals are where they are today, not because they evolved there, nor yet because of continental drift, but because they went there after the Flood.

As we have often said, creationists and evolutionists have the same data. It is how the data are interpreted that leads to differing conclusions.

See

Communication

Attenborough next discusses how animals communicate with one another. He demonstrates responses when he imitates a woodpecker’s tapping,9 when he simulates the noise of a female cicada’s wing-flick by snapping his fingers, and by howling to summon a wolf. Of particular interest is a species of monkey shown that has a single call that means “Snake!” and another single call that means “Danger from the air [or Eagle]!” And he goes so far as to label these calls “the beginning of a vocabulary”. In fact, animals communicate in many different ways, including display, body posture, gestures, facial expression, vocal calls, the emission of odours, the use of body secretions that some use to mark territories, and so on.

What animals don’t have is a grammatical language. When God made human beings, He made them (and only them) “in His image” (Genesis 1:26–27),10 and He gave the capacity for grammatical language only to mankind. Because we have this God-given ability, not only can we communicate explicitly and extensively with each other, but we can also communicate with God by prayer, and He can communicate with us via His written Word, the Bible.

Evolution, genetics and animal behaviour

Attenborough next briefly mentions Richard Dawkins’ book The Selfish Gene, which he says, “argues that it is the gene which drives evolution. The survival of an individual animal is of less importance than the survival of its genes.” He illustrates this by showing ants prepared to die in the process of defending their colony, and meerkats that cooperate for the good of the group, in both cases (he says) to ensure the transmission of the group’s genes to the next generation.

However, altruism overall is actually a problem for evolutionists. “[T]he explanation for helpful animals cannot be found in a purposeless theory like evolution, but rather in understanding that God the Creator has placed the world’s array of animals on earth for His glory and to fill particular roles in the planet’s ecology. That some creatures should help others in maintaining that role is no surprise to those who know that God—not evolution—created life on earth.”11 Evolutionary explanations for altruism, including ‘kin selection’, fall flat.

DNA

Attenborough makes the claim that humans share about 95% of our DNA with chimps. This figure has been steadily revised downwards over the years and is now reckoned to be a further 10% lower.12 Be that as it may, we also share about 50% of our DNA with bananas. As prominent evolutionist Steve Jones pointed out, “that doesn’t make us half bananas, either from the waist up or the waist down”.13

Also, investigation of the chimp Y chromosome has found that it “has only two-thirds as many distinct genes or gene families as the human Y chromosome and only 47% as many protein-coding elements as humans. Also, more than 30% of the chimp Y chromosome lacks an alignable counterpart on the human Y chromosome and vice versa.”14

See

- Genomic monkey business—estimates of nearly identical human–chimp DNA similarity re-evaluated using omitted data

- Chimp genome sequence very different from man

- Making a man out of a chimp

- Y chromosome shock

Attenborough concludes: “Our DNA extends in an unbroken chain, right to the beginning of life, 4,000 million years ago.” But he and his fellow evolutionists are unable to explain the source of our DNA. This is because the genetic code is not an outcome of raw chemistry, but of elaborate decoding machinery including the ribosome. Remarkably, this decoding machinery is itself encoded in the DNA, and the noted philosopher of science Sir Karl Popper pointed out: “Thus the code cannot be translated except by using certain products of its translation. This constitutes a baffling circle; a really vicious circle, it seems, for any attempt to form a model or theory of the genesis of the genetic code.”15,16 Natural selection cannot help, as this requires self-replicating entities—therefore it cannot explain their origin.

Actually, we should now say ‘codes’, because along the same stretch of DNA, there are also ‘epigenetic’ and ‘splicing’ codes. Multiple codes are an even bigger problem for evolution, as geneticist John Sanford, the inventor of the gene gun, pointed out:

Most DNA sequences are poly-functional and so must also be poly-constrained. This means that DNA sequences have meaning on several different levels (poly-functional) and each level of meaning limits possible future change (poly-constrained). For example, imagine a sentence which has a very specific message in its normal form but with an equally coherent message when read backwards. Now let’s suppose that it also has a third message when reading every other letter, and a fourth message when a simple encryption program is used to translate it. Such a message would be poly-functional and poly-constrained. We know that misspellings in a normal sentence will not normally improve the message, but at least this would be possible. However, a poly-constrained message is fascinating, in that it cannot be improved. It can only degenerate. Any misspellings which might possibly improve the normal sentence will be disruptive to the other levels of information. Any change at all will diminish total information with absolute certainty.

…

The poly-constrained nature of DNA serves as strong evidence that higher genomes cannot evolve via mutation/selection except on a trivial level.17

Conclusion

Sir David’s 60 years of wildlife programs, with their stunning photography, have made a remarkable contribution to our knowledge of animals worldwide. He has indeed fulfilled his ambition of bringing to our TV screens animal behaviour that has never before been filmed. However, it is sad that in all this beauty, he has not been able to see the hand of our Creator God.

When challenged on this, his reply is:

Well, if you ask … about that, then you see remarkable things like that earwig and you also see all very beautiful things like hummingbirds, orchids, and so on. But you also ought to think of the other, less attractive things. You ought to think of tapeworms.

You ought to think of a parasitic worm that lives only in the eyeballs of human beings, boring its way through them, in West Africa, for example, where it’s common, turning people blind.

So if you say, “I believe that God designed and created and brought into existence every single species that exists,” then you’ve also got to say, “Well, he, at some stage, decided to bring into existence a worm that’s going to turn people blind.” Now, I find that very difficult to reconcile with notions about a merciful God.

First, Attenborough is wrong about this worm—it doesn’t normally live in eyeballs and prefers not to. Secondly, God did not design things this way, but they became this way after sin entered the world. This is why we all (including Sir David) need a Saviour. That Saviour is the Creator, the Lord Jesus Christ.

(See also Why doesn’t Sir David Attenborough give credit to God? For more refutations of Attenborough’s claims.)

References

- Also known as the Miller-Urey experiment. Prof. Harold Urey was graduate student Stanley Miller’s supervisor at the University of Chicago. Experiments done in 1952 were first published in 1953. Return to text.

- This segment, from the BBC video, was not included in the Australian showing of this episode by Channel 10 on May 13, 2013, possibly to accommodate 16 minutes of adverts included by Channel 10. Return to text.

- Bergman, J. Why the Miller-Urey research argues against abiogenesis, J. Creation 18(2):28–36, August 2002. See creation.com/urey. Return to text.

- In Australian slang we call this ‘having two bob each way’. It means to “support contradictory causes at the same time, often in self-protection”! See dictionary.babylon.com/have_two_bob_each_way/. Return to text.

- Woodmorappe, J., review of The Cambrian Explosion: The Construction of Animal Biodiversity, by Douglas H. Erwin and James W. Valentine (2013), J. Creation 27(3), 2013 (to be published). Return to text.

- Denton, M., Evolution: A Theory in Crisis, Adler and Adler, Maryland, USA, 1985, pp. 109–10. Return to text.

- Ahlberg, E., and Clack, J.A., A firm step from water to land, Nature 440(7085):cover and pp. 747–49, 6 April, 2006. Return to text.

- Niedzwiedzki, G., et al, Tetrapod trackways from the early Middle Devonian period of Poland, Nature, 463(7277):cover and pp. 43–48, 7 January 2010. Return to text.

- See also Catchpoole, D., Woodpecker: head-banging wonder, Creation 34(3):43, 2012. Return to text.

- Cosner, L., Broken Images, Creation 34(4):46–48, 2012. Return to text.

- Doolan, R., Helpful animals, Creation 17(3):10–14, June 1995. See creation.com/helpful-animals. Return to text.

- Tomkin, J., and Bergman, J., Genomic monkey business—estimates of nearly identical human–chimp DNA similarity re-evaluated using omitted data, J. Creation 26(1):94–100, April 2012. Return to text.

- Jones, S., interviewed at the Australian Museum on The Science Show, broadcast on Australian ABC radio, 12 January 2002. See http://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/scienceshow/almost-like-a-whale/3504048. Return to text.

- Catchpoole, D., Y-chromosome shock, Creation 33(2):56, April 2011. Return to text.

- Popper, K.R., Scientific Reduction and the Essential Incompleteness of All Science; in Ayala, F. and Dobzhansky, T., Eds., Studies in the Philosophy of Biology, University of California Press, Berkeley, p. 270, 1974. Return to text.

- Sarfati, J., Self-replicating enzymes? J. Creation 11(1):4–6, 1997; creation.com/replicating. Return to text.

- John Sanford, Genetic Entropy & the Mystery of the Genome, p. 131–3, FMS Publications, Third Edition 2008. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.