Journal of Creation 16(3):116–122, December 2002

Browse our latest digital issue Subscribe

Darwin’s apemen and the exploitation of deformed humans

Diseased and deformed humans were exploited as sideshow ‘freaks’ for decades to ‘prove’ Darwinism. These displays were a major attraction of many leading circuses and shows for over a century, and likely influenced millions of people to accept evolutionism. One recent example was in 1974, and no doubt more recent ones exist. Darwin, Haeckel and Wallace discussed these examples as potential evidence for macroevolution. Although most anthropologists and textbook authors do not use circus ‘freaks’ to try to prove Darwinism, a thorough search failed to reveal even a single case where they exposed their use as fraudulent support for Darwinism. By their silence, they allowed the dishonesty to continue for decades. Some medical doctors examined these putative Darwinian missing links and verified that they were diseased but otherwise normal humans.

From the early 1800s until today, hundreds of millions of people the world over have visited amusement fairs and circuses. Circuses were the leading form of commercial entertainment for almost a century until the introduction of motion pictures.1 A major circus attraction for decades was side-show displays of a deformed human who was widely advertised as “Darwin’s missing link”, a “man-monkey”, or an “ape-man” or “ape-woman”. Actually, these shows were historically one of the most convincing evidences of Darwinism for the populace at large. These circus displays were usually deceitfully made to appear to be convincing ape-human links, as Darwin’s theory required.

It is now known that all of these claimed ‘missing link’ cases were normal humans afflicted with various genetic deformities or diseases which, in most cases, have now been accurately identified by medical researchers.2 One of the most famous circuses, Barnum and Bailey, regularly featured displays of diseased or deformed humans that they claimed proved Darwin’s theory of human evolution or, more often, dishonestly led visitors to conclude they were valid scientific evidence for Darwinism. Many of the advertisements for these exhibits were specifically designed to satisfy the public’s curiosity about Darwin. Kunhardt et al. even state that Barnum’s missing link “was strengthened by an unwitting Barnum ally, the English scientist Charles Darwin”.3

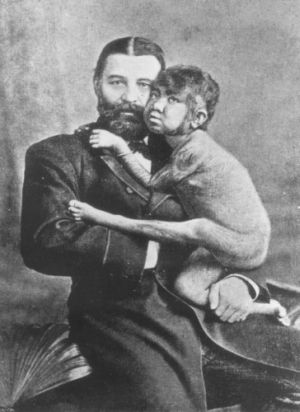

One of the first of many such ‘missing links’ was introduced in the early 1860s, just months after “the earth-shattering appearance of Darwin’s Origin of Species”.3 In what Kunhardt et al. call one of Barnum’s all-time great human presentations, Barnum’s “Man-Monkey” was depicted on advertising posters as “nothing less than the ‘missing link’”.3 This “savage creature”, immortalized by the famous American artists Currier and Ives, was claimed to have the anatomy of an orangutan and the countenance of a human. His ape anatomy was claimed to include “the perfect head and skull of the Ourang-outang, while the lower part of the face is that of the native African”.4 It was also claimed that his ears were set back too far for a human, his teeth were “double nearly all around” and as a result he could not close his mouth entirely.5 He was, the circus claimed, examined

“ … by some of the most scientific men we have, and pronounced by them to be a CONNECTING LINK BETWEEN THE WILD NATIVE AFRICAN AND THE BRUTE CREATION” [emphasis in original].5

This “great fact for Darwin” not only looked the part, but also was instructed to play the part as well—he was given a long staff to hold to imply that he did not normally stand on two legs, but rather walked like a monkey.5 Dressed in only a loincloth, he was taught “jungle language”—mostly hideous grunts—to help him act out his ape-man charade. When given a cigar, he would grunt and grin, then eat the cigar.6 A good actor, he convinced millions to believe that he in fact was an ape-man. In truth, he was an African American male dwarf named William Henry Johnson who suffered from a brain disorder now known as microcephalicism. Then called “pin-head” or “cone-head” disease, microcephalics have abnormally small brains, are retarded, and have many superficial ape-like features. Johnson’s friends claimed that he was “a good-natured imbecile who enjoyed being exhibited”.7

According to Kunhardt et al., Johnson was “enlisted into a lifetime of conspiracy” to fool the public into believing he was Darwin’s missing link.3 Billed as “a man-monkey captured while swinging from trees in an African jungle”, he was “unlike other ape men” in that he “was not so wild or brutish that he had to be chained, handcuffed, or confined behind bars”.8 He convincingly played this charade for well over half a century—from the 1860s until his death in 1926.9 Shortly before he died from pneumonia at the age of 81, he reportedly said to his sister, “Well, we fooled ‘em a long time”.9 Commonly called “Zip” or “What is it”, he was declared by Bradna to be “the greatest freak” of all time.10

Even before Darwin published his classic work, circuses in Barnum’s day were displaying alleged ape-men based on the belief (much discussed by scientists) that life

“ … might not be immutable, but subject to a process of gradual change. It was left to Wallace and Darwin to formulate the theory of natural selection, but even before the publication of the latter’s controversial Origin of Species in 1859 sufficient evidence had accumulated to convince many scientists that evolution occurred, although its mechanism was then but dimly perceived.”11

Another exhibit was of a “deformed but talented man-monkey Hervey Leach” whom Barnum attempted to pass off as “The Wild Man of the Prairies”.12 Barnum wrote the following in the advertisements announcing his show at London’s Egyptian Hall in 1846:

“Is it an animal? Is it human? … Or is it the long sought for link between man and the Ourang-outang, which naturalists have for years decided does exist, but which has hitherto been undiscovered? … Its features, hands, and the upper portion of its body are to all appearances human, the lower part of its body, the hind legs, and haunches are decidedly animal. It is entirely covered, except the face and hands, with long flowing hair of various shades. It is larger than an ordinary sized man, but not quite so tall. … its food is chiefly nuts and fruit, though it occasionally indulges in a meal of raw meat; it drinks milk, water, and tea, and is partial to wine, ale, and porter.”12

“The Wild Man of the Prairies” was later proven a fraud, and Barnum even tried to deny his involvement.

Julia Pastrana: Darwin’s missing link

Probably one of the most convincing—and also the most famous and tragic—of the Darwinian missing links was Julia Pastrana (1834–1860). Julia had an overdeveloped ape-like jaw pushed forward like a gorilla, a long beard with moustache, and her entire face and body, with the exception of the palms of her hands and the soles of her feet, was covered with thick, black, curly hair. She also had a broad, flat nose, thick lips, large ears, and in other ways was remarkably ape-like.13 Her flat nose and heavy brow ridges gave her a strong Neandertal appearance.14 These traits, plus her thick, short neck, and her four-feet six-inch height, only served to support her billing as a “semi-human … between a human being and an Ourang-outang”, an “ape-woman,” and “Darwin’s missing link”.15,16

In fact, she suffered from several genetic diseases, including a form of hirsutism (hairiness) properly called genetic hypertrichosis terminals (or polytrichosis), and associated gingival hyperplasia, a deformity that produces enormous abnormal hair growth and an ape-like protruding jaw.17–19 Julia may also have had defective ovaries, and possibly a tumour or other abnormalities that caused her ovaries to produce too many male hormones. Treatments for this condition were unknown when she was young. Julia was only one of at least 50 verified people who have suffered from hirsutism, many of whom were “entirely covered with long hair and who were taken to be specimens of Darwin’s missing link”.20 Many of them worked in circuses as “apemen or human werewolves”.21

Julia’s defective dentition included what looked like an irregular teeth arrangement, likely due to severe gingival hyperplasia (overdevelopment of the gum). Some even claimed that she had a complete extra set of normal teeth. The incorrect conclusion that she had a double set of teeth resulted from the fact that her thickened alveolar processes could be confused with teeth.22 Charles Darwin, who “certainly took an interest in her” according to Bondeson,23 perpetuated this misinformation. Darwin concluded that Julia

“ … had in both the upper and lower jaw an irregular double set of teeth, one row being placed within the other, of which Dr. Purland took a cast. From the redundancy of teeth her mouth projected, and her face had a gorilla-like appearance.”24

The cause of her teeth abnormalities could have been linked to her hirsutism, or could have been due to scurvy from a diet lacking in vitamin C when she was young.13,25 Darwin did not state if he believed she was an evolutionary link, but did not seem too concerned about her being ‘stuffed’ after her death like an animal and displayed to the public as one (see below).

Julia Pastrana usually wore costumes that exposed her legs, arms and shoulders so people could see her thick body hair, and publicity pamphlets of the time described Julia as “semi-human” and a “hybrid of a human male and an ape”.26,27 Pastrana and her ape-like fellow ‘freaks’ were sometimes billed as a “cross between a human being and an ape”, which gave an equally misleading impression that apes and humans were so close that they could interbreed. This idea further strengthened the belief that humans evolved from apes. Reode even described her as a type of ape that was “extinct ten thousand years before Adam”.28

Julia was so successful that she did not need to tour with a circus but worked on her own. When she was on stage, the audience voiced “loud gasps. One woman screamed. Another slumped fainting in her seat.”29 Because it was not sufficient for her to simply parade past the audience to display her ape-like body, she put on a real talent show. Some nations such as Germany all but prohibited ‘freak’ shows that degraded such people. To get around this problem, she danced, sang, and otherwise entertained her audience. After she had danced, “the applause was stormy, wave upon wave of it. Apewoman she may be, the audience seemed to be saying, but she can dance!”30 She also sang, often in Spanish or English, and her mezzo-soprano voice was said to be tender and sweet, emphasizing her humanity.

Drimmer claims that her success was so great that “today, more than a hundred years after her death, people still know her name”.31 The famous Italian director Carlo Ponti (1912-2007) even produced a stage play of her life titled The Ape Woman.32,33 In the play, originally released in Italian as La Donna Scimmia, a man discovers a shy, sensitive girl whose body is covered in hair, and realizes she can make him rich on the freak-show circuit. Another play based on her life by Shaun Prendergast told of her tragic exploitation.34 At least one doctoral dissertation and one book were written about her.35,36 A film directed by Marco Ferreri was made in 1964 about her life, and another that has a budget of $40 million directed by Taylor Hackford and starring Richard Gere as her manager is planned. Even poetry has been penned about her—one poem is titled “The litanies of Julia Pastrana”.37 Her early life is clouded with uncertainty. One of her managers once claimed she was discovered as an infant that had been abandoned in a remote region in Central America.13,38 More likely, she was born to a tribe of Sierra Madre Indians in the State of Sinaloa on the west coast of Mexico.39,40 Pamphlets that advertised her show claimed that her relatives

“lived in caves, in a naked state [and that] their features have a close resemblance to those of a … Orang-outang … [although] they have intellect and are endowed with speech … they have always been looked upon by travellers as a kind of link between the man and the brute creation.”44

This apocryphal explanation was fabricated to support the illusion that Julia was Darwin’s missing link. In fact, she had a job working in the governor’s house until shortly before she left for America in April of 1854.16 She actually was ‘discovered’ by a man named Retes, who persuaded her to come to the United States to be exhibited.

With the promise of a better life, Julia left Mexico with Mr Retes when she was 20. She arrived in New Orleans in October of 1854, and then headed directly for New York. Some historical accounts also speak of how she eventually learned how to read, and indulged herself in romantic novels—in her dream world she would become a beautiful and adored young woman like the heroines she read about.38,41 She gave many interviews to leading journalists, and was commonly described as good natured, gentle, affable, sociable, warm hearted, “intelligent and quick”, and in control of herself—all evidence that blatantly contradicted allegations of her ape-human status.13,42–44 She soon learned English, travelled to Europe and was put on display in London at the Regent and other Galleries.47,48

Some alleged that she was an Afro-American, implying that she was not an ape-women but a fraud. Obviously this allegation was not good for business, so her manager had her examined by a physician named Alexander B. Mott, who concluded that she was indeed a woman but a “hybrid, wherein the nature of a woman predominates over the brute—the Orang-outang”.45,46 To further bolster their claims for Julia, she also was examined by Cleveland physician S. Brainerd. It was not uncommon in the 1800s for physicians to be poorly trained, especially about genetic problems. The doctor compared Julia’s hair to that of an African under a microscope, and concluded from this ‘test’ that Julia contained “no trace of Negro blood”.49,47 It was also concluded that she was part of a “distinct species”.

Other people were less inclined to accept the evolutionary explanation. Dr Kneeland, a comparative anatomist, was asked to judge Julia’s place in the animal kingdom. His opinion was “she was entirely human”, and was not a Negro.48 British naturalist Francis T. Buckland concluded that she was “simply hideous”, but only a deformed Mexican Indian woman.49 Obviously, only the claims that supported the Darwinist’s ape-woman explanation were used for publicity, and the ape-woman claims worked—she toured both the United States and Europe for almost half a decade until she died tragically at age 28 giving birth to her first child.

Her last manager, Theodore Lent, when he learned that his star was going to leave him for another manager as had happened in the past, convinced her that he loved her, and they soon married.50 She eventually became pregnant, and it is said when she saw that her child had many of her ape-like traits, she was so distraught that she died (on 25 March 1860, only five days after his birth).13,51 The official account states that she died in Moscow, Russia, of complications following childbirth. Her last words reportedly were “I die happy; I know I have been loved for myself”.52 The death was listed as due to metro-peritonitis puerperalis.53

Any doubts about her husband’s true motives were dispelled when he allowed her body and that of their son (who lived only 36 hours) to be embalmed by a Professor Sukaloff in Moscow. Lent then displayed them for anyone willing to pay the price of admission (which was not cheap). The embalming was carried out at Moscow’s Anatomical Institute where the Professor achieved excellent results.

Lent soon also found another ‘ape-woman’ wife named ‘Zenora’, and within a few years became a wealthy man from his ape-women exhibitions. In 1884 he went insane, was committed to a Russian insane asylum, and soon thereafter died. After his death, the exhibition of the embalmed Julia and her son continued in Europe for decades. Their mummies were finally returned to America briefly in 1972 on their final tour. They then recrossed the Atlantic, and are now believed to be in the Institute of Forensic Medicine in Norway.54,55 Some people want their bodies buried in Julia’s homeland, Mexico, and others want them to be preserved so they can be studied by science.

Krao: the perfect missing link

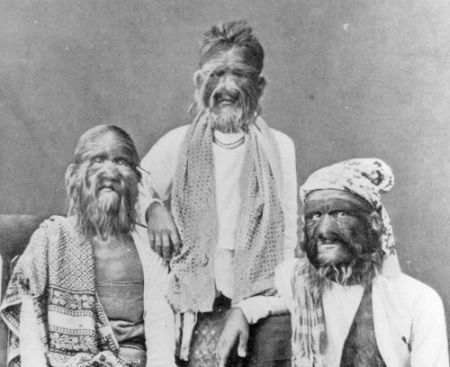

Another Darwinian ‘missing link’, a girl named Krao Farini (1876–1926), was first exhibited in Europe in the early 1880s when she was only about six or seven years old, and soon was exhibited in the United States. Krao, a native of southeast Asia, was said to be Siamese and was covered with thick, black hair. She lacked nose cartilage, and had cheek pouches that she could project forward almost to the same degree as a chimp, all of which made her look very ape-like.56 First, she was called an “ape-child”, then as she grew an “ape-girl”, and last an “ape-woman”.57 Gould and Pile describe Krao’s face as the “prognathic type, and this, with her extraordinary prehensile powers of feet and lips, gave her the title of ‘Darwin’s missing link’”.58 To better convince the public of her ape-human status she was “fraudulently presented as having pouches in her mouth, prehensile toes, cartilage in her nose, and other simian features”.59

As a young girl she was photographed in a jungle setting in poses that deliberately reinforced the public perception of her as an ape-human hybrid.60 She even was claimed to be part of a whole race of “ape-people” but the “king” of Laos would allow only Krao permission to leave Laos.61 In fact, she was a “typical Siamese” suffering from a “pathological condition”.65 The deception worked: the “hairy girl from Thailand” was “a Ringling Brothers star for years”.62 The exhibit, displayed first by a well-known London showman named Farini, was described as follows:

“It was the heyday of the controversy over Charles Darwin’s theory that man was descended from ape-like creatures (Darwin never said that man was descended from apes themselves) and his followers were constantly hoping to turn up a creature intermediate between man and the apes. To some, Krao appeared to be just what they were looking for.”63

To support the circus’ claims, a corresponding member of the Institution Ethnographique named Mr Kaulitz-Jarlow did a ‘scientific’ study of Krao when she was about six years old. He described her as particularly ape-like, having thick, jet-black smooth hair that covered her head and formed a virtual mane on her neck. He then “went on to point out in detail how closely her facial structure resembled that of the gorilla”.64 This ‘ape-like’ status and ‘missing-link’ conclusion was a “widely entertained”, but “mistaken view” that Hutchinson claimed “the newspapers helped to spread”.65

The expert further concluded that, although of a normal intelligence, fluent in several languages, well-read, and of cheerful disposition, if she was annoyed “her wild nature at once comes to the fore; she throws herself on the ground, screams, kicks, and gives vent to her anger by pulling her hair in a very particular way”.66 She even was displayed in some of the leading academic institutions of her day as a Darwinian ‘missing link’.65 Krao was a star of the Ringling Brothers, Barnum and Bailey Circus until she died on 16 April 1926 at the age of 49.

Krao’s supposed ‘ape-like characteristics’ were probably due to hirsutism, and she likely suffered from the same or similar deformities as had Julia Pastrana. Possibly, as with Julia, she had a vitamin C deficiency as a child that may have produced some of her ape-like features (such as her protruding lips).

Other Darwinian missing links

Other so-called missing links include Lionel the lion-faced man born in Poland in 1890 to normal parents. He was a featured attraction in Barnum and Bailey Circus for years. A female ‘missing-link’ named Grace Gilbert (billed as “the woolly child”) and another women called the “female Esau” (born in Michigan in 1880) both toured for years. Yet another example was Jo-Jo, the dog-faced boy who was born in Russia as Fedor Jeftichew. He was described in advertisements as a “savage” that could not be civilized. In fact, he was very civilized and spoke Russian, German, and English. One of the best examples of a Darwinian missing link was Percilla Bejano “the monkey girl”, also a victim of hirsutism. She was displayed from age 3 in shows, and died in her sleep on 5 February 2001 at age 89.67 She often appeared on stage with a trained chimpanzee to emphasize her missing-link status.

Another example, Priscilla “the monkey girl” (who looked a lot like Julia Pastrana), also called the “Gorilla Girl” and “the Goddess of terror”, toured as recently as 1974 in Maumee, Ohio, under a sign that asked “was Darwin right? Did man evolve from Ape?”68 The show claimed that she was “inspected by many, many specialists, and they all claim” that certain of her features are those “of a monkey”.69

The influence of circus ape-men on the common people

An important myth that resulted from Darwinism was that there must exist somewhere in the present or past creatures that were intermediate between humanoids and anthropoids. Related to this idea is that of devolution i.e. that our children or our children’s children may revert to the subhuman creatures that we were at one time in the past.70 Both of the ideas were exploited by circuses.

How many millions of people saw these various ‘ape-human’ exhibits, and as a result became convinced that Darwinism was true, is not known. It is known that they “made a lasting impression” on some people.71 That most all of these ape-human deformities were due to recognizable medical defects, often genetic, was well recognized even in the 1800s.28

These exhibits were not only blatantly dehumanizing, but the exhibitors in virtually all cases deceptively pawned them off to the public either as proof of Darwin’s theory of evolution, or occasionally as evolutionary throwbacks called atavisms. In the words of Odell, “the world was gradually preparing for Darwin and checking him up in terms of Barnum”.72 These ape-human exhibits were no doubt highly impressive, and very convincing, to the untrained audiences who viewed them. Otherwise, why would millions flock to see them for a price that was not cheap in its day?

In most cases, the circuses and exhibitors were not motivated primarily to prove evolution to the public. In fact, in many (if not most) cases, they knew that their exhibits actually consisted of diseased or deformed humans. In almost all cases, the primary motive no doubt was financial. Nonetheless, the end result was to help convince the common people of the truth of Darwinism, and was one more factor that was influential in causing the rapid conversion of large segments of the population to Darwinian evolution.

Even some trained anthropologists and biologists were fooled. Milner, in a study of this period, concluded that “early evolutionists thought … Julia Pastrana was a ‘throwback’ to an ape-like stage of humanity”.73 Although most anthropologists and textbook authors did not use these examples as proof of Darwinism, Darwin, Haeckel and Wallace all discussed these examples as evidence for macroevolution. One “standard anthropological text”, The Living Races of Mankind,74 contained a photograph of Julia Pastrana that has been used in some American racist publications, which claimed she was a hybrid “between a black person and an ape”.75 Darwin even described Julia Pastrana’s appearance as “gorilla-like” and as evidence of the great extent of genetic variation found in humans that would allow natural selection to select from.76 Of course, we now know that this uniqueness was not due to normal “genetic variation”, but instead was as a result of a rare disease.

Haeckel described Miss Pastrana as an ape-like human that represented “a higher stage of development” than “the long-nosed apes”.77 Topping claimed that the Chinese, for years, “thought these hairy people were a reversion to an ancestral prototype such as the ape-men”.78 I was unable to find a single case where evolutionists openly exposed these cases in print as fraudulent, and therefore as invalid support for Darwinism, even though some medical doctors examined these ‘missing links’ and verified that they were merely diseased normal humans.

Some scientists did examine individual claims, and one such study by English anthropologist professor Keane concluded that Krao was clearly of the species Homo sapiens.60,79 Rothfels notes that as a whole the

“ … scientific community and the ‘educated’ tended to frown on claims by the exhibitors of ‘savages’ and ‘ape-men’ that the freaks were in fact the much-theorized missing links. … Despite educated skepticism, however, the popular and scientific interest in ‘missing links’ rarely abated” (emphasis in original).80

By their silence, they allowed the dishonesty and outright frauds to continue for decades. Some scientists even lent their prestige and authority to the ‘missing link’ fraud.

“Showmen asked scientists to authenticate the origin and credibility, and the scientists’ commentary appeared in newspapers and publicity pamphlets. Some exhibits were presented to scientific societies for discussion and speculation. Showmen played up the science affiliation. They used the word ‘museum’ in the title of many freak shows and referred to freak show lecturers as ‘professor’ or ‘doctor’. Linking freak exhibits with science made the attractions more interesting, more believable, and less frivolous to Puritanical anti-entertainment sentiments.”81

The influence of circus ape-men on racism

Bearded ladies and ape-looking people were known long before Darwin published his Origin of the Species, and also were used as evidence of macroevolution prior to Darwin. Biological evolution ideas extend far back in history. As far back as the middle 1700s Voltaire even claimed that “the white man is to the Black as the Black is to the monkey”.82 Others had claimed that the “Negroes were a result of cross breeding between humans and Simians”. Racist ideas existed before Darwin, but things changed drastically after his works were published:

“Such racist mythology did not play a determining role in the perception of non-Europeans by Europeans until the triumph of the theory of organic evolution in Darwin’s Ascent [sic] of the Species (1859) and its extension by analogy into early developmental anthropology. … Almost all his early readers took him to be saying that beyond Homo sapiens organic evolution is neither possible nor desirable—and the struggle to survive, therefore, though it does not cease at that point, moves from the biological to the social or cultural plane. This second ‘ascent of man’, the new anthropology taught, has raised men from ‘primitivism’ or ‘savagery’ to ‘civilization’, from a culture without the alphabet or the wheel to one with a printing press and an advanced technology, from, in short, the ‘nasty, brutish and short’ life eked out in most of the world to the kind enjoyed in Europe—and after a while, the United States.”83

The racism in Darwinism, Fiedler argues, was also important in influencing, for example, the rise of racist ideas and movements such as the Ku Klux Klan. Furthermore, in the popular mind at least, convincing many people of the reality of evolution also had many unintended racist side effects that no doubt helped to legitimize movements such as the Ku Klux Klan. An example can be found in the film titled the The Birth of a Nation, when a white father says to a Harvard-educated ‘mulatto’ who had asked for his daughter’s hand in marriage:

“I happen to know the important fact that a man or woman of Negro ancestry, though a century removed, will suddenly breed back to a pure Negro child, thick-lipped, kinky-headed, flat-nosed, black-skinned. One drop of your blood in my family could push it backward three thousand years in history”.84

The effect of attempts to pass off diseased and genetically deformed persons as Darwin’s missing link also had negative, if not tragic, effects on the victims themselves. Instead of helping them to deal with their problems, it no doubt perpetuated them, producing the derogatory label ‘freak’ that made it even more difficult for them to establish reasonable normal relationships with other people.29,55 Most of “Darwin’s Ape-Men” suffered from congenital hypertrichosis lanuginosa (long non-pigmented hair over the entire body), congenital hypertrichosis terminalis (long pigmented hair over the entire body), and/or gingival hyperplasia.

The realization that these people were not missing links but medically or genetically diseased, plus the compassion of those who learned of their plight, contributed to the legislation and local sentiment that opposed displaying these people in side shows as was done previously. Various churches and church leaders have protested the display of Julia Pastrana many times during the last century because they viewed such not only as sordid, but also as degrading to humanity.85 No doubt if someone attempted a similar show today, public outrage would rapidly shut the show down as racist and fraudulent. Unfortunately, the harm is now done, and cannot easily be undone.

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank Bert Thompson, John Woodmorappe and Clifford Lillo for their comments on an earlier draft of this paper.

References

- Bradna, F. and Spence, H., The Big Top: My Forty Years with The Greatest Show on Earth by Fred Bradna as told to Hartzell Spence including A Circus Hall of Fame, Simon and Schuster, New York, 1952. Return to text.

- Thomson, R.G., Freakery: Cultural Spectacles of the Extraordinary Body, New York University Press, New York, 1996. Return to text.

- Kunhardt, Jr, P.B., Kunhardt III, P.B. and Kunhardt, P.W., P.T. Barnum; America’s Greatest Showman, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, p. 149, 1995. Return to text.

- Cook, J.W., Jr, Of men, missing links, and nondescripts: the strange career of P. T. Barnum’s ‘What is It’ exhibition; in: Thomson, Ref. 2, p. 148. Return to text.

- Saxon, A.H., P.T. Barnum: The Legend and the Man, Columbia University Press, New York, p. 99, 1989. Return to text.

- Wallace, I., The Fabulous Showman: The Life and Times of P.T. Barnum, Knopf, New York, p. 117, 1959. Return to text.

- Durant, J. and Durant, A., Pictorial History of the American Circus, A.S. Barnes, New York, 1957. Return to text.

- Lindfors, B., Africans on Stage, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, p. ix, 1999. Return to text.

- Bradna, Ref. 1, p. 242. Return to text.

- Bradna, Ref. 1, pp. 242, 318. Return to text.

- Saxon, Ref. 5, p. 97. Return to text.

- Saxon, Ref. 5, p. 98. Return to text.

- Miles, A.E.W., Julia Pastrana: the bearded lady, Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine 67(2):160–164, 1974. Return to text.

- Adams, R. (Ed.), The exploited apewomen, Mysteries of the Human Body, Time Life, New York, pp. 59–60, 1990. Return to text.

- Odell, G., Annals of the New York Stage, Vol. VI [1850–1857], Columbia University Press, New York, p. 413, 1931. Return to text.

- Laurence, J.Z., A short account of the bearded and hairy female, Lancet 2:48, 1857. Return to text.

- Bondeson, J. and Miles, A.E., Julia Pastrana, the nondescript: an example of congenital, generalized hypertrichosis terminalis with gingival hyperplasia, American J. Medical Genetics 47(2):198–212, 1993. Return to text.

- Anavi, Y., Lerman, P., Mintz, S. and Kiviti, S., Idiopathic familial gingival fibromatosis associated with mental retardation, epilepsy and hypertrichosis, Developmental Medical Child Neurology 31(4):538–542, 1989. Return to text.

- Horning, G.M., Fisher, J.G., Barker, B.F., Killoy, W.J. and Lowe, J.W., Gingival fibromatosis with hypertrichosis: a case report, J. Periodontology 56(6):344–347, 1985. Return to text.

- Drimmer, F., Very Special People; The Struggles, Loves, and Triumphs of Human Oddities, Amjon Publishers, New York, p. 126, 1973. Return to text.

- Maugh, T.H., Werewolf gene; in: Science Supplement, Grolier, New York, p. 335, 1997. Return to text.

- Bondeson, J., The strange story of Julia Pastrana; in: A Cabinet of Medical Curiosities, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, New York, pp. 216–244; 1997; p. 242. Return to text.

- Bondeson, Ref. 22, p. 223. Return to text.

- Darwin, C., The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication, D. Appleton, New York, p. 321, 1896 Return to text.

- Vogel, R.I., Gingival hyperplasia and folic acid deficiency from anticonvulsive drug therapy: a theoretical relationship, J. Theoretical Biology 67(2):269–278, 1977. Return to text.

- Drimmer, Ref. 20, p. 75. Return to text.

- Anonymous, Hybrid Indian! The Misnomered Bear Woman, Julia Pastrana, Boston, 1885, (a copy is in the Yale University Library), quoted in Adams, Ref. 14. Return to text.

- Quoted in Bondeson, Ref. 17, p. 223. Return to text.

- Drimmer, Ref. 20, p. 73. Return to text.

- Drimmer, Ref. 20, p. 74. Return to text.

- Drimmer, Ref. 20, p. 75. Return to text.

- Ferreri, M., DeFelice, L., Girardot, A., Majeroni, A., Tognazzi, U. and Azcona, R., The Ape Woman, Something Weird, Video, Seattle, 1996. Return to text.

- Ponti, C., Ferreri, M., DeFelice, L., Girardot, A., Majeroni, A., Tognazzi, U. and Azcona, R., The Ape Woman, Something Weird, Video, Seattle, 1994. Return to text.

- Mather, C., Review of ‘The True History of the Tragic Life and Triumphant Death of Julia Pastrana, the Ugliest Woman in the World’ by Shaun Prendergast, Theater J. 51(2):215–216, 1999. Return to text.

- Fuch, J., Über Trichoson, besonders die der Julia Pastrana I, University of Bonn, 1917. Return to text.

- Soho, C.H., The Singular History of Julia Pastrana, other title, History of Julia Pastrana, 1857. Return to text.

- Shapcott, T. (Ed.), The Moment Made Marvelous, University of Queensland Press, Brisbane, pp. 325–329, 1998. Return to text.

- Drimmer, Ref. 20, p. 201. Return to text.

- Bondeson, Ref. 22, p. 218. Return to text.

- Drimmer, Ref. 20, p. 76. Return to text.

- Drimmer, Ref. 20, p. 83. Return to text.

- Bondeson, Ref. 22, p. 225. Return to text.

- Van Hare, G., Fifty Years of a Showman’s Life, Sampson Low, Marston, London, p. 46, 1893. Return to text.

- Laurence, Ref. 16, p. 48. Return to text.

- Bondeson, Ref. 22, p. 219. Return to text.

- Drimmer, Ref. 20, p. 79. Return to text.

- Drimmer, Ref. 20, p. 80. Return to text.

- Bondeson, Ref. 22, p. 220. Return to text.

- Buckland, F.T., Curiosities of Natural History, Vol. 2, Bentley, London, pp. 44–51, 1865. Return to text.

- Bondeson, Ref. 22, p. 226. Return to text.

- Fiedler, L., Freaks: Myths and Images of the Secret Self, Simon and Schuster, New York, p. 145, 1978. Return to text.

- Miles, Ref. 13, p. 10. Return to text.

- Bondeson, Ref. 22, p. 229. Return to text.

- Bondeson, Ref. 22, p. 241. Return to text.

- Adams, Ref. 14, p. 60. Return to text.

- Snigurowicz, D., Sex, simians, and spectacle in nineteenth-century France; or, How to tell a ‘man’ from a monkey, Canadian J. History 34:51–81, 1999. Return to text.

- Rothfels, N., Aztecs, aborigines, and the ape-people: science and freaks in Germany 1850–1900; in: Thomson, Ref. 2, pp. 126–163. Return to text.

- Gould, G.M. and Pyle, W.L., Anomalies and Curiosities of Medicine, W.B. Saunders, p. 231, 1896. Return to text.

- Bogdan, R., Freak Show: Presenting Human Oddities for Amusement and Profit, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, p. 115, 1988. Return to text.

- Durant and Durant, Ref. 7, p. 105. Return to text.

- Rothfels, Ref. 57, p. 163. Return to text.

- Drimmer, Ref. 20, p. 219. Return to text.

- Drimmer, Ref. 20, pp. 162–163. Return to text.

- Drimmer, Ref. 20, p. 163. Return to text.

- Hutchinson, H.N., The Living Races of Mankind, Appleton, New York, p. ii, 1902. Return to text.

- Drimmer, Ref. 20, p. 163. Return to text.

- Huffines, S., On the Sawdust Trail, June, 2001, www.atomicbooks.com/shocked/0601/sawdust062001.html. Return to text.

- Levenson, R., In Search of the Monkey Girl, Aperture, Millerton, NY, p. 23, 1982. Return to text.

- Levenson, Ref. 68, p. 59. Return to text.

- Fiedler, Ref. 51, p. 241. Return to text.

- Bondeson, Ref. 22, p. 217. Return to text.

- Odell, Ref. 15, p. 413. Return to text.

- Milner, R., Julia Pastrana, The Encyclopedia of Evolution, Facts on File, New York, p. 354, 1990. Return to text.

- Hutchinson, Ref. 65, p. v. Return to text.

- Bondeson, Ref. 22, p. 243. Return to text.

- Darwin, Ref. 24, p. 321. Return to text.

- Haeckel, E., The Evolution of Man, G.P. Putnam’s Sons, New York, p. 372, 1905. Return to text.

- Topping, A., Wild men, Science Digest, pp. 66–113, August 1981; p. 113. Return to text.

- Harrison, J.P., Krao, the so-called missing link, Report of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, p. 575, 1883. Return to text.

- Rothfels, Ref. 57, p. 162. Return to text.

- Thomson, Ref. 2, p. 29. Return to text.

- Quoted in Fiedler, Ref. 51, p. 240. Return to text.

- Fiedler, Ref. 51, pp. 240–241. Return to text.

- Quoted in Fiedler, Ref. 51, pp. 241–242. Return to text.

- Bondeson, Ref. 22, p. 239. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.