Egypt and the short Sojourn

Part 2: Historical support

In part 1, we presented evidence for the ‘short’ Sojourn view, i.e., that the Israelites were in Egypt for about 215 years instead of the often assumed 430 years. We discussed several confusing and seemingly contradictory passages in Scripture. After much analysis, we concluded that the Sojourn in Egypt was the shorter of the two options. This requires that the ‘oppression’ prophesied by God started before their entry into Egypt. Instead of beginning under an unnamed pharaoh that arose after Joseph died, it would have started in Isaac’s time (Genesis 21:8–9; Genesis 26:17–22) and continued through the life of Jacob (Genesis 31:42).

Please note that, while there is still room for debate, we feel the case is leaning strongly in favour of the short Sojourn. In part 1, we mentioned a few points to show how this view intersects very nicely with a certain period of Ancient Egyptian History (AEH). In this article, we will provide many additional details.

CMI is a presuppositional ministry, meaning we hold Scripture as the primary authority when it comes to matters of secular history and dating. Our starting point is always Scripture, lest anyone think that we try to shoehorn biblical dates or events into secular archaeology, or vice versa. However, if one wants to seek synchronies between biblical events with AEH, it is necessary to understand the culture and common practices of the day. There are seeming mysteries in Scripture that Christians have been trying to solve for centuries. For example, who are the pharaohs of Joseph’s time, Moses’s early years, and the Exodus? There is a lot of information in the Old Testament about Egypt, but these pharaohs’ names are absent, which presents many difficulties.

To solve major textual riddles, one must learn as much about the Bible as possible. In the case of the relationship between ancient Egypt and ancient Israel, we truly have to dig deep, gleaning every tidbit of biblical information. We also need to do the reverse, seeking information in Egypt. For example, even a rudimentary understanding of ancient Egyptian religion and politics tells us that we should not expect a group of foreign slaves, who worshipped a foreign God, and who won a great internal victory over the Egyptians, to be mentioned on the walls of Egyptian temples and tombs that are, in turn, dedicated to their gods and their pharaohs’ military victories. For more on this see Bates, Egyptian chronology and the Bible—framing the issues.

When discussing the points of correspondence between biblical and Egyptian history, there are three issues at play: the amount of time the Israelites spent in Egypt, the timing of the Exodus, and questions about the accuracy of the standard Egyptian timeline. This has spawned much confusion, with many competing chronological solutions. Some of these solutions are better than others, but it is often difficult to sort through the details, particularly when some revisionists present their views in dogmatic, ‘I’ve solved it all’ terms.

We are going to present one historical model here. This is being done because there is no other place on creation.com where the details of this view are set out clearly. If there are many places where the secular Egyptian and short Sojourn timelines mesh, this would be good evidence that we are on the right track. We have written many articles and one book (Tour Egypt) that contain most of this information, but we wanted to have it accessible on creation.com in one place. This allows the interested reader to weigh all the evidence together and allows us to publish updates as new ideas and information arise.

Synchronizing AEH and biblical history

Before this conversation can even start, we must find an event in history that is mentioned in both the Bible and AEH. Many secular Egyptologists use the sacking of Luxor (Thebes in Greek) by the Neo-Assyrian king Ashurbanipal in 663 BC as an anchor point. Therefore, AEH after this date must be fairly accurate. But CMI has done much original work on the biblical Pharaoh Shishak (from the time of Rehoboam and Jeroboam; 1 Kings 12; 2 Chronicles 12), confirming that he was identical to the Third Intermediate Period (3IP) Pharaoh Shoshenq I.

See:

- See Was Pharaoh Shoshenq—the plunderer of Jerusalem?

- Strengthening the Shishak/Shoshenq synchrony

- Shunning the Shishak/Shoshenq synchrony?

The biblical date for Shishak’s invasion of Judah is 925/6 BC and the standard AEH date is 925 BC. Thus, the earliest historical peg is centuries earlier than many assume. This means there are only c. 500 years from the earliest clear link between Egyptian and biblical history and the time of the Exodus (1446 BC).

Table 1 shows the standard, secular AEH chronology. This is based primarily on the lost writings of an Egyptian priest named Manetho who compiled a list of 30 Egyptian dynasties. See the aforementioned Egypt chronology article by Bates to see how the dates were derived and note that we do not agree with this dating scheme, as the earliest dates are pre-Flood.

Table 1: Secular/Standard dating of Egyptian History

Note: These dates are in constant flux.

A dynasty usually refers to a sequence of rulers from the same family or group.

| DATE | PERIOD | DYNASTIES |

|---|---|---|

| Pre 3200 BC | Predynastic/Prehistory | |

| 3200–2686 BC | Early dynastic Period | 1st–2nd |

| 2686–2181 BC | Old Kingdom | 3rd–6th |

| 2181–2055 BC | 1st Intermediate Period | 7th–10th |

| 2055–1650 BC | Middle Kingdom | 11th–12th |

| 1650–1550 BC | 2nd Intermediate Period/Hyksos | 13th(?)–17th |

| 1550–1069 BC | New Kingdom | 18th–20th |

| 1069–664 BC | 3rd Intermediate Period | 21st–25th |

| 664–525 BC | Late Period | 26th |

| 525–332 BC | Achaemenid/Persian Egypt | 27th–31st |

| 332–30 BC | Ptolemaic/Greek Egypt | |

| 30 BC–641 AD | Roman & Byzantine Egypt |

When were the Hebrews in Egypt?

For reasons given in our prior article, we believe that the arrival, oppression, and Exodus of the Hebrews took place within an approximately 215-year period that began in the Second Intermediate Period (2IP) and ended during the 18th Dynasty of the New Kingdom Period. We have no major issues with the later parts of AEH. They are the best attested to, with a wealth of historical artefacts. For example, we can be certain of the dates of the Roman occupation and the Greeks prior to that. Then we have our anchor point of 925 BC, and before that, the pharaohs of the New Kingdom have all been attested to. Indeed, most of their mummies are on display in the museums of Egypt. Although there is an obvious need to reduce the timeline of AEH, it cannot easily be done in these later eras, as Rohl1 and others seek to do. We believe the dates from the New Kingdom onward are accurate to within a few tens of years at worst. We are aware of a couple of co-regencies, for example, that are listed sequentially, where in fact, they overlap. See Table 2 for a guide on where AEH most likely aligns with biblical history.

Table 2: Aligning ancient Egyptian and biblical history

| BIBLICAL EVENTS | PERIOD |

|---|---|

| Tower of Babel/Early post-Flood | Predynastic/Prehistory |

| Mizraim settles in Egypt | Early dynastic Period |

| Terah’s descendants (Genesis 11:27–32) | OLD KINGDOM |

| 1st Intermediate Period | |

| Call of Abram. Abraham visits Egypt. | MIDDLE KINGDOM |

| Joseph in Egypt. Israelites arrive. | 2nd Intermediate Period/Hyksos |

| The pharaoh ‘who did not know Joseph’. Enslavement of the Hebrews. Birth of Moses. The Exodus. The period of the judges. |

NEW KINGDOM |

| Solomon begins the temple. Shishak plunders the divided Kingdoms of Israel and Judah. | 3rd Intermediate Period |

| Temple destroyed by Nebuchadnezzar | Late Period |

| Jews return to Israel | Achaemenid/Persian Egypt |

| Alexander conquers Egypt. Intertestamental period. |

Ptolemaic/Greek Egypt |

| Birth of Jesus Christ c. 4 BC. Church age begins AD 33. |

Roman & Byzantine Egypt |

Dating the Exodus

The Exodus occurred about 500 years before Shishak/Shoshenq ransacked Israel and Judah. This does not tell us exactly when the Exodus occurred, however. To obtain that number, one must work backwards from some fixed point. This could be Shishak’s invasion of Judah in 925/6 BC or the destruction of Jerusalem by the Babylonians in 586/7 BC. Starting with the latter, if you add up the length of reigns of the kings of Israel and Judah, you can estimate that Solomon became king about 970 BC.2 We then read:

In the four hundred and eightieth year after the people of Israel came out of the land of Egypt, in the fourth year of Solomon’s reign over Israel, in the month of Ziv, which is the second month, he began to build the house of the Lord (1 Kings 6:1).

The fourth year of Solomon's reign would be 966 BC. Subtracting 480 years from 966 BC gives us the Exodus date of 1446 BC. Note that this date could easily be off by a few years. There are many areas of uncertainty inherent in the calculation, but many scholars are comfortable with the given number.3

This would put us somewhere in the middle of the 18th Dynasty of the New Kingdom period (keeping in mind a few years of wiggle room either way). This is during the reign of Amenhotep II, our candidate for the pharaoh of the Exodus (see later).4

Yet, many scholars prefer a ‘late date’ for the Exodus of approximately 1225 BC, during the time of the 19th Dynasty’s Rameses II (‘Rameses the Great’) or one of the other 20th Dynasty ‘Ramesside’ kings (which would make it even later). Rameses II has often been cited as the pharaoh of the Exodus because (1) he was known as a great builder (indeed, his monuments are all over Egypt), (2) the city of Pi-Rameses was built up and made into the capital during his reign, (3) the Bible says the Hebrews were tasked with building projects, and (4) there are clear biblical statements that the Hebrews built the store cities of Pithom and Raamses (Exodus 1:11; cf. Exodus 12:37; Numbers 33:3). A 1225 BC Exodus would have the Israelites entering Egypt either in 1440 BC (under Amenhotep II, with a short Sojourn) or 1665 BC (during the 2IP, with a long Sojourn). Interestingly, many of the points we are making about the arrival of the Israelites in Egypt would also fit with a view that combines a late Exodus with a long Sojourn. However, multiple additional points contradict this view.

Note, however, that Rameses II cannot be both the pharaoh of the oppression and the pharaoh of the Exodus. Why? Because the first pharaoh, from whom Moses fled, died before Moses was called back to Egypt (Exodus 2:15, 23; 4:19)! Many people skim past this requirement and, following Hollywood, imagine the same pharaoh at both times.

There remains a major problem, however, because Genesis tells us that the Israelites settled in the land of Rameses during the time of Joseph, who entered Egypt hundreds of years before any Ramesside king took the throne:

Then Joseph settled his father and his brothers and gave them a possession in the land of Egypt, in the best of the land, in the land of Rameses, as Pharaoh had commanded (Genesis 47:11).

During the Hyksos5 occupation (2IP), the city was known as Avaris. It is not in doubt that it was later expanded and renamed Raamses by Rameses II.6 Today, it is called Tell el Dab’a.

However, while it is true that no known pharaoh was named ‘Rameses’ that early in Egyptian history, it is also true that we do not know the names of every pharaoh. Also, the name Ramose, which is linguistically similar, was given to the son of Ahmose, the first king of the famous ‘Thutmosid’ 18th Dynasty (see later). Thus, it is not like the name was unknown. Following the old adage that an absence of evidence is not evidence of absence, it is a mistake to claim it is ‘impossible’ that the Egyptians called the place Raamses.

Alternatively, it is most likely somebody (e.g., Joshua, Samuel, or a group of knowledgeable and capable scribes) updated the biblical text. Even though some feel uncomfortable with this concept, there are numerous places where the copyists updated the names of places in the texts, to be contemporaneous at the times they were writing. Here are some examples.

- Genesis 14:14 mentions the city of Dan. This was the endpoint of the first phase of Abram’s pursuit of Lot’s captors. The city would not get that name until many years later when the tribe of Dan migrated north and took the city, almost certainly after the death of Joshua and perhaps not until the twelfth century BC (Joshua 19:47; cf. Judges 1:34; 18).7

- Moses’ death is recorded in Deuteronomy 34:1–12. Even though Moses is credited with writing Deuteronomy, he cannot have recorded his own death!

- Joshua 15:8; 18:28, and Judges 19:10 all add “that is, Jerusalem” when the city of Jebus is named. It was not called Jerusalem until David captured the city about 400 years after Joshua’s time.

Although Moses is given credit for the compilation of the Torah, it is absolutely clear that the first five books of the Bible contain such updates. For more details, see The Inspiration of Scripture comes in various forms and the detailed discussion of Pi-Rameses in part 1.

Another example of how names change through time involves modern-day Luxor in Egypt. During the Greek/Ptolemaic (300s BC) period, it was known by the Greeks as Thebes (possibly derived from their pronunciation of the Demotic Egyptian word for temple, “ta ipet”). The Hebrew Bible called this city “No” and associated it with its chief deity Amun (e.g., the prophecies against it in Jeremiah 46:25 [600s BC], Ezekiel 30:14–16 [500s BC], and Nahum 3:8 [612 BC]). “No” is derived from Egyptian na.t which means “city”, specifically Thebes. The ancient Egyptians called Thebes wꜢs.t (conventionally pronounced “Waset”).

The biblical use of ‘Rameses’ before Rameses I came to the throne has caused many scholars to conclude that the earlier biblical books must have been written long after the dates the books themselves claim, e.g., during or after the Babylonian captivity. Yet, those same books contain information about names, places, cultures, and common ancient practices that someone living centuries later would simply not be able to know.8 Thus, the simplest solution is that the books were written when they say they were written, and then a scribe or group of scribes updated them to arrive at their final form. Spelling changes, changing the form of the Hebrew letters used, and adding small editorial comments (e.g., “and so it is called to this day”) all accord with the Chicago Statement on Inerrancy. It is also the final form of each book that is inspired.

Aligning biblical and secular Egyptian history

What follows is a discussion of many things that align perfectly when one adopts a short Sojourn and a 1446 BC Exodus. We will take the secular timeline of AEH roughly as-is in its later periods. There are problems with the standard AEH timeline, granted, but most of those are in the earlier periods. For example, the pre-Dynastic period, the 2nd Dynasty, and the First Intermediate Period (1IP) are poorly attested in archaeology. They are not much more than a sequential list of kings given to us by Manetho, with little archaeological attestation. Also, the timing of the ending of the Middle Kingdom has changed over the years. The beginning of the Second Intermediate Period (2IP) is yet another area of debate. This was a time when a group of Semitic immigrants, called ‘Hyksos’ and ‘Asiatics’ by the Egyptians,9 ruled Egypt. As already mentioned, the latter periods have much better evidence and strong synchronisms between the Bible and the archaeological record, so we disagree that one can dramatically reduce the timeline in the middle of the 19th (NK) or 21st (3IP) Dynasties, as David Rohl attempts to do.10

For example, starting at the end of the 2IP, the New Kingdom, Third Intermediate Period (3IP), Persian, Ptolemaic, and Roman periods are the best attested periods of AEH due to the incredible wealth of archaeological artefacts, and because they are the most recent. One cannot easily erase hundreds of years of Egyptian history during these periods (see Egyptian chronology confusion: why are there so many differences of opinion?). Yes, the timeline needs to be reduced, but no, this is not the place to do it.

The 1446 BC Exodus occurs somewhere in the middle of the 18th Dynasty of the New Kingdom. Assuming a short Sojourn of 215 years, this places Joseph’s arrival in the 2IP.

Joseph and his chariot?

Many places in Scripture indicate Joseph was not interacting with a native Egyptian pharaoh prior to the time of the Hyksos. For instance, Joseph rode in a chariot (Genesis 41:43, 46:29). It is well known that chariots were not introduced into Egypt until the 2IP, along with the composite bow and improved metal weapons. This was when Egypt was dominated by the Hyksos. All those famous pictures of pharaohs riding chariots while shooting arrows at their enemies postdate the 2IP! See Bates, Did the Exodus lead to the Hyksos Invasion?

There are three options here (note that we reject option 1 and are skeptical about option 2):

- The Bible is wrong about Joseph riding in a chariot, e.g., the writer of Genesis introduced an anachronism. This is akin to the many medieval paintings of biblical scenes that include soldiers dressed in medieval armor. Such a depiction is not artistically wrong, but putting Joseph in a chariot raises questions about how much the writer of Genesis knew about the situation at the time of Joseph.

- The original text was updated to include a comparable term used later. This is possible, but if nothing like a chariot was in use at the earlier time, it would be very awkward to introduce the concept into the text. Such updates are too often anachronistic.

- Joseph actually rode in a chariot and, thus, could not have been in Egypt prior to the 2IP.

The issue of chariots is not some minor detail. Ancient Egyptians did not even have a word for chariot prior to the 18th Dynasty. CMI’s Gavin Cox notes:

I confirmed this with a search using the online Thesaurus Linguae Aegyptiae. Here I found 37 entries for vocabulary connected with chariots, or their parts, none of which occurs before the New Kingdom [which is immediately after the 2IP]. In other words, before the New Kingdom, there is no vocabulary to even describe what a chariot is, anywhere, in all the texts ever discovered by scholars in Egypt!11

The long Sojourn (combined with the clear biblical evidence for the ‘early’ 1446 BC Exodus) would place Joseph in the Middle Kingdom. Since chariots did not appear in Egypt until the 2IP (under Hyksos rule), this would place Joseph in Egypt more than two hundred years before chariots arrived. This cannot be correct. Joseph must have arrived in the 2IP or later. This contradicts articles that have appeared in our own Journal of Creation,12 so we advise people to read carefully. Joseph’s association with chariots also destroys the popular idea that he can be equated with the famous 3rd Dynasty priest/architect Imhotep.13 Several people have attempted this,14,15 but the data presented here rule out the association entirely.

Joseph’s original master was singled out

Joseph’s original master was Potiphar, who is continually singled out in Scripture as ‘the Egyptian’. For example:

Now Joseph had been brought down to Egypt, and Potiphar, an officer of Pharaoh, the captain of the guard, an Egyptian, had bought him from the Ishmaelites who had brought him down there. The Lord was with Joseph, and he became a successful man, and he was in the house of his Egyptian master (Genesis 39:1–2, emphasis ours).

And:

From the time that he made him overseer in his house and over all that he had, the Lord blessed the Egyptian’s house for Joseph’s sake; the blessing of the Lord was on all that he had, in house and field (Genesis 39:5, emphasis ours).

It seems a bit redundant to continually repeat “the Egyptian” when Joseph is living and working in Egypt, unless Potiphar is also operating under the rule of a non-native Egyptian pharaoh, i.e., a Hyksos.

Pharaoh lauds a foreign god?

And Pharaoh said to his servants, “Can we find a man like this, in whom is the Spirit of God?” Then Pharaoh said to Joseph, “Since God has shown you all this, there is none so discerning and wise as you are. You shall be over my house, and all my people shall order themselves as you command. Only as regards the throne will I be greater than you” (Genesis 41:38–40).

This is the antithesis of the whole structure of native AEH, where their gods, the pharaoh, and the economy were completely intertwined and self-serving. To laud a foreign god would be to undermine the whole ‘system’, an unthinkable thing for a pharaoh to do to his priests and his subjects. He would be effectively undermining himself and the Egyptian priestly system. This is a serious consideration and strongly indicates that the pharaoh was non-Egyptian.

Yet, even if the pharaoh was an Asiatic (Hyksos) who believed in a single deity, he still may not have used exactly the name of the God of the Israelites. After all, God had not yet revealed the meaning of his name Yahweh to Moses (Exodus 3:14–15), but note that the use of the root word ‘yah’ in personal names of the era is yet another indication for the early (c. 1446 BC) Exodus date.16 But the author of Genesis puts the name Elohim in the mouth of this pharaoh (vv. 38 and 39), the very same name as the Creator in Genesis 1. This could be a translation for whatever word the pharaoh used or meant, but there is no way to translate the head of the Egyptian pantheon (e.g., Ra, Ptah, Atum, Amun, Amun-Ra, etc., depending on which period of Egyptian history we are dealing with) into Elohim without breaking important religious ideas. The whole point of the passage is that Pharaoh is singling out Joseph’s God, who truly reveals dreams, unlike any of the Egyptian gods or their supposed emissaries (Genesis 41:8). Politically, if Pharaoh was Hyksos and not an Egyptian, he could have also used this situation to his advantage, denigrating the weakling gods of the Egyptians and elevating Elohim. Placing Joseph in the 2IP turns this obscure reference into a powerful refutation of Egyptian religion.

Furthermore, it is highly unlikely that an Egyptian pharaoh would ever say that the Spirit of God dwelt in one of his servants! In ancient Egyptian religion, it was the pharaoh who was the intermediate and representative between the gods and his people. He was considered a living god by Egyptian priests and his subjects. His job was to maintain maat or balance in all of nature (note that most of the Egyptian deities represented facets of nature). Maat is represented as a feather in hieroglyphics and, at the end of his life, it was believed that a pharaoh’s heart would be weighed on a set of scales against the feather of maat to determine if he had done a good job.

Also, this is Semitic language: the word for God (el) used here is a common name of God or a ‘god’ among various Semite and Canaanite cultures. This specific divine name does not appear anywhere among the vast list of names known in the Egyptian pantheon. Any Egyptologist would see the use of the phrase “a man like this, in whom is the Spirit of God” as entirely alien to everything known about Egyptian religion and politics. This makes them think the story is entirely fictitious, devoid of historical truth. So, either the Israelites made the whole thing up, or the pharaoh was not a native Egyptian, rather a fellow Semite, a.k.a. a Hyksos!

Were the Hebrews an abomination to the Egyptians?

After Jacob and Joseph’s brothers and family are welcomed into Egypt, consider the passage where Joseph eats in the presence of his brothers:

They served him [Joseph] by himself, and them [the brothers] by themselves, and the Egyptians who ate with him by themselves, because the Egyptians could not eat with the Hebrews, for that is an abomination to the Egyptians (Genesis 43:32).

If the Hebrews were an abomination to the Egyptians, then so was Joseph. Hence, he ate by himself. Yet, the Hyksos would have had many Egyptians in their employ. The presence of Egyptian servants does not mandate that we are dealing with Egyptian rulers.

Shepherds are an abomination to the Egyptians?

In Genesis 46:31–34 we read:

Joseph said to his brothers and to his father’s household, “I will go up and tell Pharaoh and will say to him, ‘My brothers and my father’s household, who were in the land of Canaan, have come to me. And the men are shepherds, for they have been keepers of livestock, and they have brought their flocks and their herds and all that they have.’ When Pharaoh calls you and says, ‘What is your occupation?’ you shall say, ‘Your servants have been keepers of livestock from our youth even until now, both we and our fathers,’ in order that you may dwell in the land of Goshen, for every shepherd is an abomination to the Egyptians.’”

Why on earth would Joseph say that unless the pharaoh was not an Egyptian? In fact, the Hyksos were a Semitic people, much like the Israelites. Native Egyptian records show them immigrating into Egypt during the Middle Kingdom, which precedes the 2IP. To win favour, Joseph told his father to tell the king that they were shepherds, unlike the Egyptians.

But Pharaoh himself is a keeper of flocks?

The land of Egypt is before you. Settle your father and your brothers in the best of the land. Let them settle in the land of Goshen, and if you know any able men among them, put them in charge of my livestock (Genesis 47:6).

Note Pharaoh’s request for an able sheepherder to look after his own flocks. This makes little sense if he was an Egyptian because, earlier, we read that sheepherders are an abomination to Egyptians.

The best of the land for the Hebrew (foreigners)

In this same passage, Pharaoh gives Joseph ‘the best of the land’ (Genesis 45:18). This is simply an unthinkable thing for an Egyptian pharaoh to do. His land was ‘blessed’ and virtually every aspect of nature had an Egyptian god (sky, land, the Nile, etc.). Native Egyptians despised foreigners because they were not ‘blessed’. The pharaoh was the intermediate between the gods and his people. His job was to maintain maat. This is indicated later when we see the Hebrew’s God executing judgment on the ‘gods of Egypt’ (Exodus 12:12, Numbers 33:4). By humbling the gods of the natural world, God was also defeating Pharaoh as their representative. In a comparable passage we read:

Then Joseph settled his father and his brothers and gave them a possession in the land of Egypt, in the best of the land, in the land of Rameses, as Pharaoh had commanded (Genesis 47:11, emphasis ours).

Again, this is more evidence of a textual update, because how could they be settling in the land named after a Ramesside king, hundreds of years before one ever existed?

Unfortunately, many lay Christians who try to revise AEH fail to appreciate AEH culture and the political/religious/economic system under which it operated. When understood properly, one can make better sense of the passages where the Hebrews interact with the non-native Egyptians (the Hyksos) and the native Egyptians.

Joseph appointed as vizier

In the aforementioned passage (Genesis 41:43), we read:

And he made him [Joseph] ride in his second chariot. And they called out before him, “Bow the knee!” Thus he set him over all the land of Egypt.

We dealt with the issue of chariots earlier, but did Pharaoh really appoint a previously unknown foreigner to rule over all the land of Egypt? If he was Egyptian, this would have been a huge assault on a priestly religious system going back in an unbroken chain for close to a thousand years. To undermine the Egyptian gods in such a way would have been sacrilegious, particularly when the whole political and religious system is based upon the receiving of favour from the gods and the gods’ divine representative (pharaoh). In a sense, if the pharaoh was an Egyptian, he would have been undermining the very system that put him there. Then again, in a later period, a Semitic vizier who worshipped a god name El served under Amenhotep III and Akhenaten,17 two pharaohs known for their monotheism not long after the Exodus (see below). Despite the parallels, this could not be Joseph. For one, the Israelites carried Joseph’s bones with them when they left Egypt (Exodus 13:19), but this man’s body and entrails were found in his tomb.

The Egyptian priest Manetho purportedly wrote about the Hyksos:

From the regions of the East, invaders of obscure race marched in confidence of victory against our land. By main force they easily overpowered the rulers of the land. They then burned our cities ruthlessly, razed to the ground the temples of the gods, and treated all the natives with a cruel hostility, massacring some and leading into slavery the wives and children of others. Finally, they appointed as king one of their number whose name was Salitis. He had his seat at Memphis [near Cairo, which controlled the entire Delta region], levying tribute from Upper and Lower Egypt, and leaving garrisons behind in the most advantageous positions. Above all, he fortified the district to the east, foreseeing that the Assyrians, as they grew stronger, would one day covet and attack his kingdom. In the Saite nome [administrative district] he found a city very favorably situated on the east of the Bubastite branch of the Nile and called Auaris [Avaris] after an ancient religious tradition.18

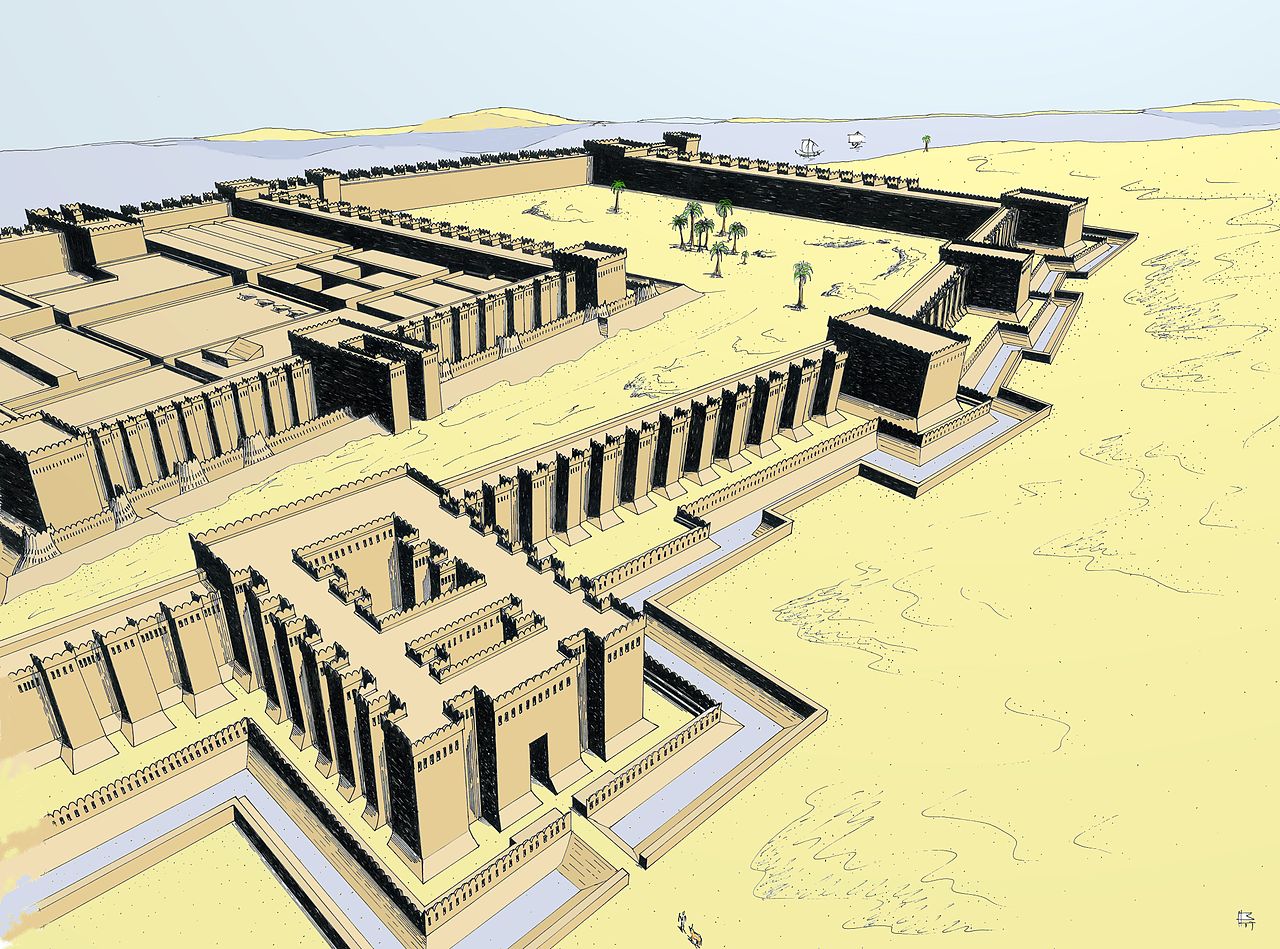

Note also that Pharaoh gives the Israelites the land of Goshen (situated in the fertile north-eastern Nile delta). He does not tell them to move into a neighborhood but to take over a large area. First, this tells us that there were probably more than 70 people among the migrating group. Second, the Hyksos came from the east (the Levant) and would have been aware of threats from that direction. Pharaoh placed the Israelites in a border region as a buffer, as if he was shoring up his unprotected eastern flank as the Hyksos were putting pressure toward the west (Memphis). This fits the geopolitical situation of the day. All of this concurs with Manetho’s location and with archaeological excavations in the area of Tell el-Dab’a (ancient Avaris). This is not some small site. Work has been continuing there for around 70 years (including by world-renowned archaeologist Manfred Bietak since the 1980s) and only a fraction of the site has been excavated. It is massive.

Interestingly, these archaeological excavations have demonstrated that a free, non-Egyptian, Semitic people lived in the area under a separate status. The statues they left behind have distinctively different hairstyles, and their homes have the classic ‘four-room’ style seen later all over Israel. If they were not the Hebrews, they were certainly not Egyptian-like.

The Hebrews lost their guardians

The Hyksos ruled Egypt from the north (Delta) region for over 100 years. After being invaded from the south by the Nubians, the native Egyptians only controlled central Egypt, with Thebes (Luxor) as their capital.19 Yet, the Egyptian records tell us they paid tribute to the Hyksos. Kamose, the last pharaoh of the native Egyptian 17th Dynasty in Thebes bemoaned this state of affairs:

I should like to know what serves this strength of mine, when a chieftain in Avaris, and another in Kush, and I sit united with an Asiatic [north] and a Nubian [south], each in possession of his slice of Egypt, and I cannot pass by him as far as Memphis [north] … No man can settle down, when despoiled by the taxes of the Asiatics. I will grapple with him, that I may rip open his belly! My wish is to save Egypt and to smite the Asiatic.20

This would also fit the events of the famine, where it tells us that the Egyptians were selling their land to the pharaoh at the time of Joseph (Genesis 47:13-31).

Eventually, and after many attempts, the Egyptians expelled the Hyksos, losing two kings in the process (Seqenenre Tao and his oldest son Kamose).

In our model, the victorious native Egyptians who had been relegated to Luxor would have found another group of detestable foreigners living off their blessed land—the Hebrews. Ahmose, younger brother of Kamose and the first pharaoh of the New Kingdom’s 18th Dynasty, was the one who successfully expelled the Hyksos and most likely enslaved the Hebrews. Scripture says:

Now there arose a new king over Egypt, who did not know Joseph (Exodus 1:8).

Ahmose is a natural candidate for ‘the king who did not know Joseph’. This idea makes sense of a baffling passage, because in a dynastic line, succession is always passed to family members or senior members of a pharaoh’s government. If this was the case with a native Egyptian dynasty, how could a pharaoh not know who Joseph (the great saviour of Egypt) was?

A change in Egyptian foreign policy

One reason the New Kingdom period was so wealthy was due to the expansion of their borders. Although they regularly traded with other nations, the Egyptians before the New Kingdom did not have much need to conquer other countries. They had incredible mineral wealth and, of course, the Nile and its lifegiving fertile silt, due to its annual flooding. We read several times in Scripture that, when there was famine or drought in the land, people went to Egypt (Genesis 26:2; 42:5) because they had food. But after being taken over by the Hyksos, it is likely that the Egyptians did not want to be ‘sitting ducks’ again. ‘The Napoleon of Egypt’—Thutmoses III—certainly enacted this policy. He is our candidate for the pharaoh who tried to kill Moses while the Hebrews were being enslaved (oppressed). Thutmoses III conducted 17 military campaigns into what is modern-day Syria/Palestine and Upper Nubia (Sudan), expanding Egypt’s empire to its largest ever extent. The rulers of various city-states in Canaan became vassals to Egypt after the campaigns of Thutmoses III.

Under which pharaoh was Moses born?

The name “Moses” fits perfectly among the Thutmosid 18th Dynasty names (e.g., Ahmose and his brother Kamose, Thutmose I–IV, etc.). There is no other period in Egyptian history where such names are found in close association. Moses means ‘son’ or child, which in Egyptian hieroglyphics is written as 𓀀𓀔𓋴𓄟. For instance, Thutmose means ‘son of Thoth’, the ibis god.

Moses seems to be an Egyptian name but, in Hebrew, Moses sounds like the verb ‘to draw out’, which fits the circumstance of his being plucked from the water. Moses’ mother placed him among the reeds21 in the Nile, somewhere in the area of Goshen (Exodus 1:15–2:10). The Bible’s use of the name Moses may also represent a clever pun on the Egyptian name, but without the attached pagan god’s name, rather as an insult to the Egyptian gods who remained nameless.

In ancient times, one of the major branches of the Nile flowed right through Goshen, and an 18th Dynasty palatial compound was constructed on top of the former Hyksos capital of Avaris, in Goshen.

In Acts 7, Stephen said:

Pharaoh’s daughter adopted him and brought him up as her own son. And Moses was instructed in all the wisdom of the Egyptians, and he was mighty in his words and deed (Acts 7:21–22).

Moses was adopted by Pharaoh’s daughter. The timeline places the infant Moses and a famous female ruler who was to become queen (Hatshepsut) in the same time and place. We do not know that it was this princess that adopted Moses, but any male Hebrew that was adopted into the royal family would have been a threat to the power structure. Hatshepsut served as coregent with her stepson, Thutmose III, who was only two years of age when he inherited the throne. She later served as a queen in her own right, before finally relinquishing control. Years later, during the reign of Amenhotep II (the likely pharaoh of the Exodus), a massive campaign to erase her from history occurred. Her temples were desecrated, her statues demolished, and her name and image (in cartouches, for example) were chiseled out. Egyptians believed that one’s image and name had to exist in this world in order to exist in the afterlife. Thus, erasing her name and image would punitively condemn her to no afterlife. This was possibly retribution for her role in raising Moses.

Some suggest that it was Thutmoses III who attempted to erase Hatshepsut’s legacy due to his antipathy towards her becoming queen while he was supposed to be king. This is unlikely, as he also served as Hatshepsut’s head of her military. This is hardly a role you would give someone who resents you, particularly given Thutmoses III’s incredible military successes! Thutmose III also married the daughter of Hatshepsut, Neferure.

Can we determine the pharaoh of the Exodus?

To figure out who was pharaoh when the Exodus occurred, we first need to look at the events preceding the Exodus. Moses left Egypt after murdering an Egyptian (Exodus 2:11–22). After 40 years in Midian (a region likely to be located in NW Saudi Arabia today) as an outlaw, God appeared to Moses:

And the Lord said to Moses in Midian, “Go back to Egypt, for all the men who were seeking your life are dead” (Exodus 4:19).

We are not told how many men were seeking to kill him, or for how long they had been dead, but the long reign of Thutmose III is a natural candidate for the 40-year exile. If Moses was raised in the royal family, it would be fair to presume that only the king could order a warrant for his death. Scripture confirms that there was a royal price on his head:

When Pharaoh heard of it, he sought to kill Moses. But Moses fled from Pharaoh and stayed in the land of Midian. And he sat down by a well (Exodus 2:15, emphasis ours).

Plus, we are told specifically that this pharaoh died before God spoke to Moses from the burning bush.

During those many days the king of Egypt died, and the people of Israel groaned because of their slavery and cried out for help. Their cry for rescue from slavery came up to God (Exodus 2:23).

Additionally, Thutmoses III is the only pharaoh besides Rameses II to reign over 40 years, although part of that was during his coregency with Hatshepsut.

Regarding the 10th plague:

So Moses said, “Thus says the Lord: ‘About midnight I will go out in the midst of Egypt, and every firstborn in the land of Egypt shall die, from the firstborn of Pharaoh who sits on his throne, even to the firstborn of the slave girl who is behind the handmill, and all the firstborn of the cattle’” (Exodus 11:4–5, emphasis ours).

Note that the text indicates Pharaoh’s son will die, but not Pharaoh himself, indicating that Pharaoh was not a first-born son. If Thutmoses III was the pharaoh of Moses’s oppression, it was his successor (see Exodus 2:23) that Moses and Aaron encountered when Moses returned to Egypt. Yet, Thutmoses III’s firstborn son (Amenemhat) died before his father. It was the second born son, Amenhotep II, who inherited the throne. This would have made Amenhotep II figuratively ‘immune’ to the 10th plague.

Amenhotep II’s firstborn son, however, would not have been so lucky. Indeed, Exodus 11:4–5 and 12:29 claim that the firstborn son of Pharaoh died. Hence, the next pharaoh, Thutmoses IV, was not the oldest son. This is confirmed by the famous Dream Stele that was found between the paws of the Sphinx. Thutmose IV placed it there. It explains how he rose to power despite not being the oldest son and describes him thus:

The King of Upper and Lower Egypt, the lord of the Two Lands, Menkheperure Thutmosis, the appearance of appearances, bestowed with life…22

There is no other place in Egyptian history where it is known that a long-reigning pharaoh (40-plus years) was succeeded by a pharaoh who was not a firstborn son, who was then succeeded by another pharaoh who was also not a firstborn son.

Interestingly, excavations at Tell el-Dab’a (ancient Avaris) have shown that the area seems to have been abandoned very quickly. Ceramic and pottery finds at the time of this abandonment do not postdate the reign of Amenhotep II, in the mid-18th Dynasty (see later).23

But isn’t Amenhotep’s mummy in the Egyptian museum of civilization?

It is a common misconception that the pharaoh of the Exodus drowned with his army in the Red Sea, but the Bible does not actually say this:

So Moses stretched out his hand over the sea, and the sea returned to its normal course when the morning appeared. And as the Egyptians fled into it, the Lord threw the Egyptians into the midst of the sea. The waters returned and covered the chariots and the horsemen; of all the host of Pharaoh that had followed them into the sea, not one of them remained (Exodus 14:27).

Note that it is Pharaoh’s army that drowned. Psalm 106:11 is often cited as a proof text that Pharaoh also died in the Red Sea. It says:

And the waters covered their adversaries; not one of them was left.

Again, Pharaoh is not mentioned, and it appears that this is simply referring only to those who were pursuing the Hebrews. Similarly, Psalm 136:15 says:

but [God] overthrew Pharaoh and his host in the Red Sea, for his steadfast love endures forever.

Petrovich writes:

A cursory reading of the text leads most to believe that because God “overthrew” Pharaoh and his army, both parties must have died. However, the Hebrew verb נער (n’r, “he shook off”) shows that God actually ‘shook off’ the powerful pharaoh and his army, who were bothersome pests that God—whose might is far greater than theirs—merely brushed away. The same Hebrew verb is used in Psalm 109:23, where David laments, “I am gone like a shadow when it lengthens; I am shaken off like the locust.”

But how could Egypt reach a ‘golden age’ so soon after it was destroyed?

Clearly, the plagues devastated Egypt. Crops were ruined, farm animals died in droves, and many people died (in the hail and when all the firstborn males died on Passover night). Pharaoh’s elite chariot division was also lost in the Red Sea. Yet, the New Kingdom was one of the most glorious periods in all Egyptian history. Worse, the Exodus supposedly occurred in the middle of this period. Why is there no evidence of a sudden decline in Egyptian power and wealth?

Several people have suggested that the weakening of Egypt after the Exodus led to the collapse of the Middle Kingdom and taking over of Egypt by the Hyksos (2IP).24 While this seems like an easy solution, the timing and accessory biblical details simply do not fit. And the regular flood of the Nile, along with Egypt’s vast mineral wealth, meant it could soon recover, so even the devastation of the plagues did not necessarily mandate a total collapse of Egyptian society.

Consider that World War I killed at least 20 million people (including soldiers and civilians on both sides) in Europe. That was 3 to 4% of the population of the major countries involved. Yet, 20 years later, Europe was engulfed in another disastrous war, World War II, where another 35 to 60 million people died (worldwide). Clearly, it does not always take centuries for a country to recover from devastation. The same could be true of Egypt. While the fields and people were decimated, the infrastructure survived. Also, the fields of Goshen were untouched.

Consider also that the army that went into the Red Sea could not have been the total forces of all Egypt. No country keeps all its military forces in one location. Although Exodus 14:7 does seem to indicate it was all of Pharaoh’s chariots (600 in total). Chariots were the elite force and likely stationed with Pharaoh’s palace. (And remember, this chariot technology was appropriated from the Hyksos in the first place.) The border fortresses along to the Mediterranean coast (on the east and west sides of the delta) would have remained staffed and provisioned. The local garrisons in each of the major cities would not have been called out. For example, a massive fort called Buhen was located south of modern Aswan some 1,500 km from Avaris. It held approximately 3,500 soldiers. It is simply not feasible to suggest that the Exodus pharaoh marshalled troops from this part of the country to pursue the Hebrews. Thus, not all of Pharaoh’s army perished in the Red Sea.

And it would have taken a very long time for messages to travel from Goshen to southernmost Egypt, on the border with Sudan, where a force of several thousand soldiers was always stationed. Clearly, only the local levee, just Pharaoh’s elite chariot guard, participated. Granted, this would have been a substantial army, but it would have been but a fraction of Egypt’s armed forces.

Finally, this was not the only major disaster to occur in Egyptian history. The Nile, for example, did not always flood, and sometimes the flooding was too long and too extensive. After such years, massive famines swept the country. Indeed, they recorded these events on their own monuments. Yet, recovery always followed destruction and that recovery was sometimes swift.

What happens in Egypt after the Exodus?

We can see the effects of the Exodus on Egyptian foreign policy. Prior to the Exodus, Thutmose III conducted multiple military raids, bringing lots of booty, but he only brought back 2,214 captives. By contrast, there was a dramatic reversal in foreign policy by his son Amenhotep II, our candidate for the pharaoh of the Exodus. Amenhotep II conducted only two (at most three) campaigns and brought back 101,000 people! This is all documented on their ‘booty lists’ engraved on walls at the Temple of Karnak, in Luxor. This dovetails nicely with the depopulation of Goshen and the Egyptian leaders needing to replace the mudbrick-making population that once lived there. Note: there are wandering Habiru/Apiru (Hebrews) listed among the slaves that were brought back. These could have been generic Hebrews (e.g., descendants of Eber), but the Israelites were wandering in the areas that Pharaoh raided at this time, and they were Hebrews (cf. Genesis 14:13). Also note that this helped depopulate Canaan so that the Israelites had an easier time invading a few decades later.

There was also a religious change in Egypt after 1446 BC. The great grandson of the presumed Exodus pharaoh was born Amenhotep IV, but he later changed his name to Akhenaten. This was the famous ‘heretic king’ who worshipped a single deity, the Aten. Akhenaten dismantled the religious system that had been in place for over 800 years. He moved the capital from Luxor and built an entirely new city called Akhetaten, meaning ‘The Horizon of the Aten’. He wrote loving psalms to the Aten that often mirror what we read in Scripture in terms of a mutual ‘loving’ relationship with his god. Recent discoveries, however, suggest that this change did not commence with Akhenaten, but with his father, Amenhotep III (grandson of Amenhotep II). Near Luxor, archaeologists have recently discovered Amenhotep III’s Golden City of the Aten. It looks like the religious change, or at least the elevation of the Aten, started earlier, with Akhenaten’s father.

It should also be noted that Amenhotep III’s father (Thutmoses IV) could have been alive at the Exodus. Either way, Amenhotep III was not distantly removed from the time of the Exodus. He would have been acutely aware of recent history, when the Egyptian gods were humiliated (cf. Exodus 12:12) and may have been seeking a new religion. Egypt’s recent brush with the all-powerful God of the Hebrews could have easily inspired the new monotheism.

Strangely, both Amenhotep III and his son Akhenaten were not as militarily active as their predecessors. In particular, they both ignored pleas for help from their vassal states in Canaan, who were complaining that a mysterious people called the Habiru or Apiru were invading. We know this from a trove of cuneiform tablets found in Egypt at Amarna (among the ruins of Akhetaten). Why did these two pharaohs sit back and squander the territorial gains made by Thutmose III?

For example, letter EA 271, which was sent to either Akhenaten or Amenhotep III25 from Milkilu, King of Gezer, says:

… So may the king, my lord, save his land from the power of the Apiru.

Joshua 10:33 tells us that Joshua killed the king of Gezer, leaving no survivors from that battle. But the Canaanites were not entirely driven out of Gezer (Joshua 16:10; Judges 1:29).

Letter EA 288, sent to Akhenaten from the city of Jebus (later to be named Jerusalem), says:

I am at war. I am situated like a ship in the midst of the sea. … now the Apiru have taken the very cities of the king.

Likewise, King Rib-Hadda of Byblos (a city on the Philistine coast) wrote to Amenhotep III saying:

…since your father’s (Thutmose IV) return from Sidon, from that time the lands have been joined to the Habiru.

The Amarna letters place an invasion of non-Canaanite people, coming from the east, at the same time the Israelites would be invading Canaan, given a short Sojourn.

If this is not the Israelites, there was an Israelite-like people doing Israelite-like things in the same area and at about the same time the Bible places them. At what other time could the invasion under Joshua have happened? Note that the king of Byblos claims the lands have been “joined” to the Habiru. In other words, the area had not just been overrun but was also now under their control. This is the rise of a new nation. If it is not Israel, who else could it be at this time in history?

What were the aftereffects of the Exodus in the surrounding regions?

The timing is perfect for the Habiru of the Amarna letters to be the Israelite Hebrews entering Canaan after 40 years wandering in the desert. The fact that these pharaohs allowed their foreign possessions to be taken away by the Habiru could be an indication that they did not want to deal with them, since they were the same people who had thoroughly embarrassed the kingdom just a few decades earlier. Therefore, we are most likely looking at Egyptian references to the Conquest period of Canaan by the Hebrews.

Several scarabs were found nearly a century ago in the cemetery of ancient Jericho. The latest of these was from the reign of Amenhotep III.26 Two scarabs, one dated to the 2IP and one dated to Amenhotep II’s reign,27 have been found in the ruins of Khirbet el-Maqatir, which some scholars believe to be the biblical site of Ai. This is just west of Jericho and was the second city in Canaan conquered by Joshua. These artifacts do not fit the ‘late’ Exodus date of c. 1200 BC, unless archaeologists have misdated the destruction layers by centuries. Another scarab from the time of Thutmose IV was found at Hazor (northern Israel), which was also conquered (twice) by the Israelites.28 Finding the name of a post-Exodus, even post-Conquest, pharaoh is not necessarily a contradiction. These scarabs are used as time markers. They could not be in those cities prior to the existence of the pharaoh in question and they fit the thought that those pharaohs were ruling at the time of the destruction of these cities.

The fourth pharaoh of the 19th Dynasty (Merenptah, who ruled c. 1213 to 1203 BC) erected a huge Victory Stele that mentions Israel directly:

The princes are prostrate, saying ‘Peace!’ Not one raises his head among the Nine Bows. Desolation is for Tjehenu; Hatti is pacified; Plundered is Pa-Canaan with every evil; carried off is Ashkelon; seized upon is Gezer; Yanoam is made non-existent; Israel is laid waste—its seed is no more; Kharru has become a widow because of Egypt. All lands together are pacified. Everyone who was restless has been bound.29

This does not fit a 1225 BC Exodus well at all. As stated earlier, Rameses II cannot be both the pharaoh of oppression and the pharaoh of the Exodus, because the pharaoh of the oppression died while Moses was in Midian. Yet, the next pharaoh (Merenptah) only reigned for about 10 years. There is not enough time during his reign for the 40 years of wilderness wandering plus the time it took to consolidate control over the land of Canaan under Joshua. Neither is there enough time between Rameses II and Merenptah for all that plus Moses’ 40 years in Midian.

The mention of Israel as an established people group early in the 19th Dynasty is yet more circumstantial evidence that the Exodus took place earlier in the 18th Dynasty and that Canaan had now been conquered by the Hebrews. Egypt is recognizing Israel as a formidable foe already settled in the Levant.

The Merenptah Stele was long thought to be the earliest mention of Israel in archaeology. However, the oldest known Egyptian inscription referring to Israel occurs on a temple built by Amenhotep III at Soleb, Nubia. While describing the surrounding nations and the directions in which they lived, mention is made of the ‘nomads of Yahweh’ who lived to the north (of Nubia). Being that his father, Thutmose IV, only reigned about 11 years, it is quite possible that the Israelites were still wandering the desert after the Exodus (which occurred during the reign of his grandfather, Amenhotep II) when the temple was built. Hence, they were still ‘nomads’. Another 18th Dynasty mention of Yahweh was recently discovered on a well-preserved Egyptian ‘book of the dead’ scroll. In Israel, the earliest mention of Yahweh was found on a lead ‘curse’ tablet found on Mt Ebal, dramatically confirming Deuteronomy 11:29. Combined, the archaeological evidence strongly militates against the ‘late’ Exodus date (c. 1267 BC) and places the Exodus squarely in the 18th Dynasty.16

Who was the pharaoh of Abraham’s time?

If we assume the short Sojourn, Abraham received the promise from God 430 years prior to the Exodus. This would have been around 1876 BC. Tentatively, this would be during the dynasties of the Middle Kingdom, well after the Great Pyramids had been built. Remember, these earlier dates are more fluid. If they vary by a few tens of years, the candidate for Abraham’s pharaoh changes. Yet, in the conventional chronology, 1876 BC would place Abraham close to the reign of the Egyptian Pharaoh Sesostris III, who had a lengthy reign of nearly 40 years. A long Sojourn would place Abraham 215 years earlier, during the chaotic First Intermediate Period (1IP) where multiple kings ruled simultaneously in different regions and, thus, it would be extremely speculative to suggest a candidate.

Why no mention of the Hebrews in Egyptian monuments?

One of the reasons for the wealth of historical artefacts from ancient Egypt is due to their religious beliefs. Their entire life was spent in preparation for the afterlife. As soon as a pharaoh ascended to the throne, he set about building his mortuary temple, where his body would lie in state for 70 days and be prepared for mummification. Similarly, lavish tombs were constructed where he would be buried with many of his earthly possessions. Pharaohs also ensured that statues or painted images of themselves would adorn the various temples. Along with these images, their names would be inscribed in cartouches. Preserving a body, an image and a name were important in ensuring that they would actually exist in the afterlife. To speak a person’s name, for example, was to give them life. We mentioned that the ancient Egyptians generally despised and looked down upon foreigners. It is very rare, for example, that one would even find the name of a foreign king on a pharaoh’s monument—even the ones that they traded with and were relatively friendly to. To do so would be to give a foreigner or an enemy ‘life’. So, how reasonable is it to expect that one would find records of a slave class (the Hebrews) appearing on monuments to deify the pharaoh and to exalt his gods?

Another point is that pharaohs did not record their defeats. Even stalemates are portrayed as glorious victories. For example, Rameses II famously made a peace treaty with the Hittites after basically losing the battle of Kadesh in Syria (1275 BC). In a prime example of political ‘spin’, his famous temple at Abu Simbel in far southern Egypt has depictions of him running over his enemies, jumping out of his chariot to personally smite them, and pulling far ahead of his troops while steering his chariot with the reigns tied about his hips. That kind of person is not going to say anything about losing to a bunch of shepherds.

The plagues God brought against Egypt were actually an assault on nature and, therefore, the gods of Egypt themselves. The ancient Egyptians had gods for virtually all aspects of nature such as the sky, the Nile, livestock, and light itself. The plagues rendered them all impotent, including the great Egyptian sun god, Ra, when God plunged Egypt into darkness (Exodus 10:21). God says in Exodus 12:12:

“For I will pass through the land of Egypt that night, and I will strike all the firstborn in the land of Egypt, both man and beast; and on all the gods of Egypt I will execute judgments: I am the Lord” (emphasis ours).

Thus, as the pharaoh’s job is to maintain maat in the created order, God’s judgment undermined Pharaoh’s role and threatened the very existence of the intertwined religious, political and economic system of Egypt. It’s not surprising, therefore, to find no record of the Hebrews and the Exodus in Egyptian records!

Moses omits the Pharaohs’ names

Egypt is mentioned 291 times in the Pentateuch (the first five books of the Bible) and 79 times in the book of Genesis alone. Yet, the actual names of the pharaohs are never stated. Later, the names of five pharaohs are given. We read about Pharaohs Shishak/Shoshenq 1 (1 Kings 11:40; 2 Chronicles 12:2), Tirhakah/Taharqa (2 Kings 19:9; Isaiah 37:9), Hophra/Apries (Jeremiah 44.30), Neco/Necho II (2 Kings 23:29; 2 Chronicles 35:20; Jeremiah 46:2), and So/Osorkon IV (2 Kings 17:4). Each of these pharaohs can be attested to by Egyptian monuments and artefacts and their placement in AEH also fits the biblical timeline.

It is generally agreed by conservative scholars that Moses is the compiler/author of the Pentateuch. There are likely several reasons why he did not mention the pharaohs’ names.

First, the Egyptian word for ‘pharaoh’ (pr-ꜤꜢ), derives from an Old Kingdom word that literally means ‘great house’ (‘house’–pr + ‘great’–aa). In the Old Kingdom, the word was used just for the royal palace. Petrovich writes:

The dynastic title, ‘pharaoh’, derives from the word that literally means, ‘great house’. During Egypt’s Old Kingdom (ca. 2715–2170 BC), the word was used of the royal palace. Not until sometime during the middle of the 18th Dynasty, slightly before the reign of Thutmose III (ca. 1506–1452 BC) … the standard practice of Thutmose III’s time was to leave enemy kings unnamed on official records.30

This gives us another indicator of timing. By leaving the pharaoh unnamed in Scripture, Moses was treating the ruler as his enemy, which reflected the standard practice at the specific period of time when we believe Moses was in Egypt.

Third, it was Egyptian practice not to combine ‘pharaoh’ with a personal name until some time later.

Finally, in the Egyptian way of thinking, to name someone is to give ‘life’ to that person. A person’s name/identity, which in Egyptian is called the ‘ren’ (rn), is just one component of many that Egyptians believed formed part of a person’s soul, which they viewed as composed of two major components, the ka and ba). Earlier, we read Stephen’s discourse in the book of Acts, where he said Moses was raised and trained in all the ways of the Egyptians, and in the royal household itself. Why would Moses mention the names of the enemies and persecutors of the Hebrews? They believed that, if Moses named them, he would be dignifying them with life. Not mentioning them, therefore, was a not-so-subtle diss on Egyptian religion. Effectively, he was doing to them what he knew they would do to the Hebrews.

Conclusions

In this article series, we have provided a brief summary of several seeming mysteries regarding the timing of the Exodus, its length, the period in which it occurred, and the major historical players. Two key issues have been explored that assist in determining the timing. They are the length of the Sojourn and a possible textual updating of the word Avaris to Pi-Rameses. After addressing these two key points, we then examined the remaining details. In the 18th Dynasty we found characters and events that fit:

- The Bible describes a friendly pharaoh in Joseph’s time, who may have been a Semitic, non-Egyptian Hyksos who controlled all of Egypt from their capital in Avaris, or from the more central city of Memphis.

- A ‘pharaoh that did not know Joseph’ fits with Ahmose, the first king of the 18th Dynasty who expelled the Hebrew-friendly Hyksos. Ahmose, or his successor, then enslaved the Hebrews who were left behind.

- The sixth pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty, Thutmoses III, ruled for more than 40 years and is the best candidate for the pharaoh who sought to kill Moses.

- The next pharaoh, Amenhotep II, was not a first-born son and so would have survived the 10th plague. He is most likely the pharaoh of the Exodus. The next pharaoh, Thutmoses IV, was also not a first-born son, because his older brother would have died in that plague. In the whole of the New Kingdom period, there is no other time when a king ruled for over 40 years and was then succeeded but two pharaohs who were not first-born sons. This perfectly fits the biblical narrative.

- Likely post-Exodus events, such as the elevation of a single deity and monotheistic religion under Amenhotep III and his son Akhenaten. The Soleb inscription’s mention of the ‘Nomads of Yahweh’ under the reign of Amenhotep III. The Amarna letters sent to Thutmoses IV, Amenhotep III, and Akhenaten from vassal states appealing for help against the marauding Habiru (Hebrews) during the likely conquest period of Canaan. The first mention of the nation of Israel under Merenptah of the subsequent 19th Dynasty, all fit the timing of a 1446 BC Exodus in the middle of the 18th Dynasty under Amenhotep II.

- The short Sojourn ideally fits the timing of these events and the characters just prior to, and up to and after the biblical dates of the Exodus, 1446 BC.

References and notes

- Egyptologist David Rohl disputes the Shishak/Shoshenq connection in the 3IP and, thus, tries to reduce the 3IP by some 200 years. Return to text.

- Hardy, C. and Carter, R., The biblical minimum and maximum age of the earth, J. Creation 28(2):89–96, 2014. Return to text.

- For more details on dating the Exodus, see Hardy and Carter (ref. 2) and Bates, G., Was Pharaoh Shoshenq—the plunderer of Jerusalem? creation.com, 28 May 2020. Return to text.

- We give credit to Dr Douglas Petrovich for initially alerting us to his views on the Exodus pharaoh. Though we do not concur with his view of the length of the Sojourn, we do concur with his views on the Pharaoh of the Exodus. Return to text.

- Hyksos means ‘rulers of foreign lands’. Return to text.

- There are various ways to spell the name Rameses when translating from either hieroglyphics or Hebrew. For example, the ESV spells רַעַמְסֵֽס as ‘Rameses’ in Gen 47:11, Ex 12:37, Num 33:3, and Num 33:5 but spells it ‘Raamses’ in Exodus 1:11. These variations are in the ancient Hebrew vowel points and so carry over into our modern English versions. Return to text.

- Based on Judges 18:31, the migration of the tribe of Dan must have taken place before Shiloh was destroyed (early to mid-eleventh-century BC), but it probably took place after the time of Deborah’s statement in Judges 5:17 about Dan remaining with the ships (alluding to their original coastal allotment). The archaeological evidence at Dan is consistent with Israelites conquering the city in the thirteenth or early twelfth-century BC and bringing with them a different culture that originated in the south. One argument for dating the migration sooner is based on Judges 18:30, that it was contemporary with a grandson of Moses. But it is debatable whether Jonathan was truly a grandson of Moses since there are textual variants in the ancient manuscripts, and Moses was not the only one to have a son named Gershom. It is also possible that Jonathan was a later descendant of Moses if v. 30 skips any generations (cf. 1 Chronicles 23:15–16 which omits Jonathan). Return to text.

- For example, Joseph’s brothers sold him for 20 silver shekels (Genesis 37:28). How would a later author have known that 20 shekels was the average price for slaves in the 18th century BC? Hammurabi even stated this in his famous law codes. Indeed, the price for a slave was lower than that in earlier times and significantly higher afterwards. Even the Bible indicates the price went up over time (Exodus 21:32). See biblearchaeology.org/research/patriarchal-era/2312-the-joseph-narrative-genesis-37-39-50. Return to text.

- The Egyptian phrase for ‘Hyksos’ is heqa khasut, or ‘rulers of foreign lands’. Manetho misinterpreted the Hyksos as ‘shepherd kings’, a claim later repeated by Josephus, although this does befit their Levantine origins. Return to text.

- His view is problematic in several respects, including the fact that he believes the biblical Shishak is not the traditional Shoshenq 1 of the 3IP, but instead is Rameses II. This would mean that the famous Israel Stele of Pharaoh Merenptah (the son of Rameses II, where he mentions the nation of Israel) would post-date Solomon in Rohl's view. Placing Saul and David in the time of the 18th Dynasty and Solomon at the beginning of the 19th undermines many of the powerful evidences for the United Monarchy of Israel that are contemporary with the later 3IP. Return to text.

- See Cox., G. Shunning the Shishak/Shoshenq synchrony? J. Creation 36(2):40–49, 2022. Return to text.

- E.g., Clarke, P., Joseph’s Zaphenath Paaneah—a chronological key, J. Creation 27(3):58–63, 2013. Return to text.

- Imhotep is credited with the design of the Step Pyramid of Djoser and the enclosing temple complex. This was the first time large blocks were used in construction, yet the joints between the blocks are perfectly flat, to the point where a piece of paper cannot even be inserted between them. This is important, because if two stones under a heavy burden are not perfectly in contact, cracks will propagate from the misaligned portions and potentially cause the entire structure to collapse. He made other amazing contributions and was highly revered in Egypt even centuries later. Return to text.

- Habermehl, A., Revising the Egyptian chronology: Joseph as Imhotep, and Amenemhat IV as Pharaoh of the Exodus, 7th International Conference on Creationism, article 38, 2013. Return to text.

- Wyatt, M.N. (wife of Ron Wyatt), arkdiscovery.com. Quoted in Clarke, ref. 12. Return to text.

- Cox, G., Biblical chronology and the oldest ‘Yahweh’ and ‘Israel’ inscriptions: their significance for the traditional 1446 BC Exodus date, J. Creation 37(1):45–54, 2023. Return to text.

- Zivie, A., Pharaoh’s man, ‘Abdiel: the vizier with a Semitic name, Biblical Archaeology Review 44:4, 2018. Return to text.

- Manetho, Aegyptiaca, frag. 42, 1.75–79.2, touregypt.net/manethohyksos.htm, accessed 2 January 2020. Return to text.

- This explains the shift from burying kings and queens near Giza (e.g., the location of the Great Pyramids) to the Valley of the Kings (e.g., where King Tut’s tomb was found) far to the south. Return to text.

- Translated from the Carnarvon Tablet. Gardiner, A., Egypt of the Pharaohs, 1961, reprint Oxford University Press, 1979, p. 166. Return to text.

- To keep him from floating downstream, unlike the depictions seen in popular movies! Return to text.

- Dream Stela – Translation, ancient-egypt.org/language/anthology/fiction/dream-stela/dream-stela---translation.html, 9 Nov 2014. Return to text.

- Petrovich, D., Toward pinpointing the timing of the Egyptian abandonment of Avaris during the middle of the 18th Dynasty, J. Ancient Egyptian Interconnections 5(2):9–28; 2013. Return to text.

- Down, D., Unwrapping the Pharaohs, Master Books, Green Forest, AR, 2006; see also Bates, G., Did the Exodus lead to the Hyksos Invasion? creation.com, 29 Oct 2020. Return to text.

- EA 271 doesn’t use the name Akhenaten, but the tablet was found in Akhenaten’s palace and was addressed to “the king, my lord, my god, my Sun”, which is appropriate for Akhenaten. Return to text.

- There is considerable controversy about this claim mainly because it comes from John Garstang (1876–1956). Some of his views are quite controversial among modern archaeologists. We will have to wait for the scholars to come to a consensus. See Sanders, M.S., Jericho part IV – the archaeology, biblemysteries.com/lectures/jericho4.htm, accessed 10 December 2019. Return to text.

- Stripling, S. and Hassler, M., A clear conquest pattern, patternsofevidence.com/2019/02/16/clear-conquestpattern, 16 February 2019. Return to text.

- Petrovich, D.A., The dating of Hazor’s destruction in Joshua 11 via biblical, archaeological, and epigraphical evidence, biblearchaeology.org/research/conquest-of-canaan/2454, 6 January 2011. Return to text.

- Rohl, D., A Test of Time, The Bible—From Myth to History, Volume One, Century, chap. 7, p. 168, 1995. Return to text.

- Petrovich, D., Amenhotep II and the historicity of the Exodus pharaoh, biblearchaeology.org/research/chronological-categories/exodus-era/3147-amenhotep-ii-and-the-historicity-of-the-exodus-pharaoh, 4 Feb 2010. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.